Did you know that ghost stories and yokai (monsters) were extremely popular during the Edo period? What we now consider a summer tradition actually originated in the Edo period. As society transitioned from the chaos of the Warring States period to a time of peace, common people developed a growing interest in the unknown. Tales of terror told at dusk and sightings of ghosts became not only a form of entertainment but also a mirror reflecting the darker sides of society. But why did yokai and ghost stories become so popular during the Edo period, to the point of becoming a boom? In this article, we delve into the mystery of the yokai and ghost story boom in the Edo period.

What Exactly Are Yokai?

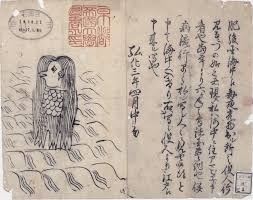

So, what exactly are yokai? In Japanese folklore, yokai are entities that cannot be explained by common sense or natural laws. They are beings endowed with mysterious powers that cause bizarre and abnormal phenomena. When objects inexplicably disappeared in homes or strange water sounds were heard by the river, people imagined and passed down stories of zashiki-warashi (house spirits) or kappa (water creatures). These beliefs are deeply rooted in Japan’s animism and the concept of “yaoyorozu no kami” (eight million gods).

The origins of yokai date back to ancient times. In the Nara period, texts such as the “Kojiki” and the “Nihon Shoki” featured great serpents and demons. During the Heian period, collections of tales like the “Konjaku Monogatari” and the “Uji Shūi Monogatari” recorded yokai, although their appearances were not depicted. From the Kamakura to the Muromachi periods, the appearance of yokai began to be illustrated in narrative paintings and picture scrolls, particularly in the “Tsukumogami Emaki,” which depicts tools transforming into yokai.

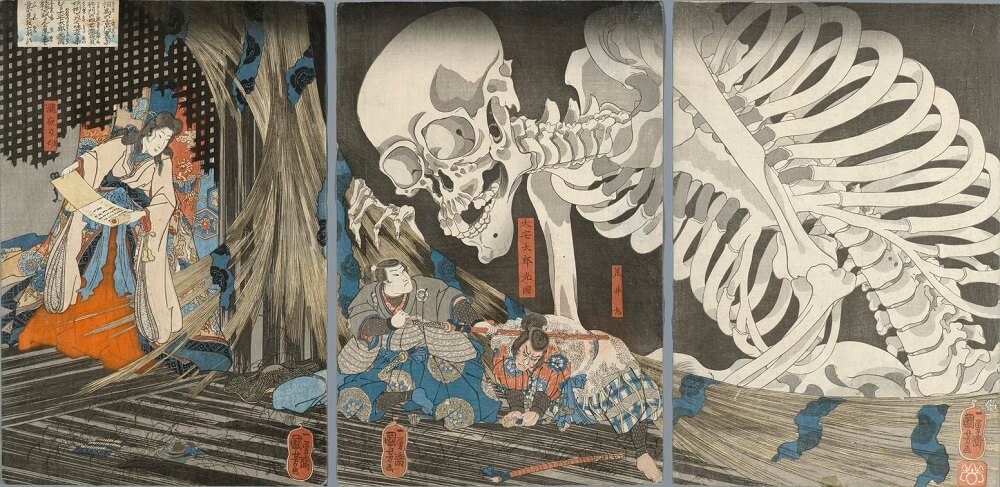

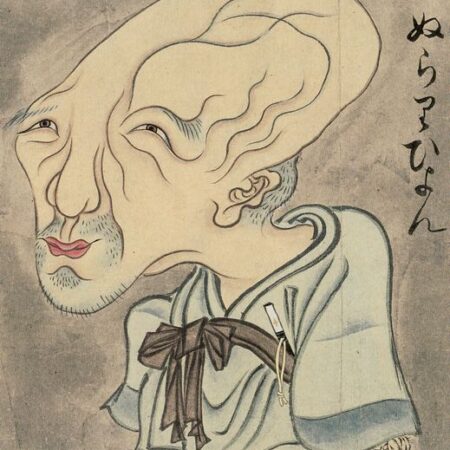

In the Edo period, a yokai boom occurred, and many ukiyo-e artists began depicting ghosts and yokai. Works by artists such as Hishikawa Moronobu and Utagawa Hiroshige feature a wide variety of yokai, ranging from terrifying to cute. These ukiyo-e significantly influenced the formation of modern, imaginative images of yokai.

Why Did Yokai and Ghost Stories Become Popular During the Edo Period?

So why did yokai and ghost stories become a major boom in the Edo period? Here, we introduce several reasons why the yokai and ghost story boom occurred in the Edo period.

Peace

The Edo period was a time of approximately 260 years of peace following the end of the Warring States period. This long period of peace, sometimes referred to as “peace-induced complacency,” allowed the common people to be free from the anxieties of war and conflict, enabling them to enjoy daily life with leisure. A peaceful society provided an environment conducive to the development of culture and the arts, allowing people to spend time on entertainment. As a result, the culture centered around yokai greatly developed, creating a fertile ground for yokai-themed entertainment to be widely accepted by the common people.

The Development of Natural History and the Birth of the Yokai Encyclopedia “Gazu Hyakki Yagyo”

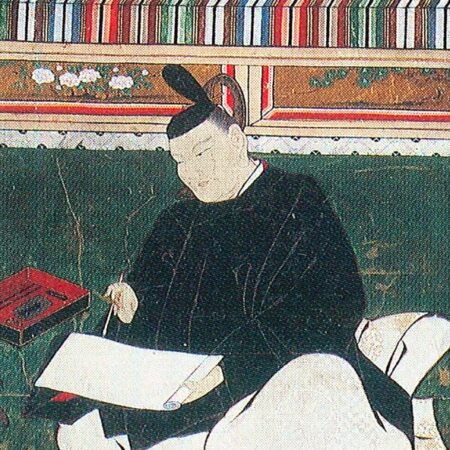

The encouragement of natural history (natural sciences) by Tokugawa Yoshimune during the Kyōhō reforms also influenced yokai culture. Yoshimune implemented policies such as conducting nationwide surveys of local products, expanding the Komaba and Koishikawa medicinal gardens, and relaxing the ban on Chinese translations of Western books. Remarkably, this survey also included yokai. Past literature and folklore were referenced to identify yokai by name, appearance, and behavior. As a result, the yokai encyclopedia “Gazu Hyakki Yagyo” by Toriyama Sekien was published. This encyclopedia featured one yokai per page, depicting their names and appearances, allowing anyone to visually enjoy the characteristics of yokai.

The Development of Entertainment and Culture

The significant development of yokai-themed entertainment in urban areas of the Edo period was also a major factor in the boom. Ghosts and yokai appeared in various forms of popular entertainment, such as magic shows, shadow pictures, kabuki, and rakugo, spreading a culture of enjoying fear as entertainment. Particularly in “yellow-covered books” (kibyoshi), yokai were depicted as comical and satirical characters, enjoyed as entertainment for knowledgeable and educated adults. In these books, yokai were portrayed as beings that inverted human societal values, providing humor and satire.

Following the failure of the Tenpō reforms, satirical prints and toy pictures became widespread in the late Edo period. Satirical prints featuring yokai were extensively used to criticize societal and political issues. For example, Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s “Minamoto no Yorimitsu and the Earth Spider” depicted yokai symbolizing the common people who fell victim to the reforms, causing a significant impact. Additionally, children’s toys such as “monster sugoroku” and “ghost karuta” were mass-produced, making yokai popular characters among children.

Japan’s Three Great Ghost Stories

During the Edo period, ghost stories were immensely popular, and among them, the most famous are known as Japan’s Three Great Ghost Stories. Here, we introduce these three legendary tales.

The Ghost Story of Yotsuya

During the Genroku era, Tamiya Matazaemon, a low-ranking samurai official living in Yotsuya, had a daughter named Oiwa who suffered from poor eyesight. Matazaemon wished to retire and have a son-in-law take over, but Oiwa contracted smallpox, which left her disfigured.

Years later, Matazaemon passed away, and his friends tried to find a husband for Oiwa, but her appearance deterred any suitors. They eventually hired a smooth-talking man named Iemon, deceiving him into marrying Oiwa. Upon seeing her, Iemon was shocked but couldn’t back out. He endured for a while but gradually began to resent her.

Iemon then met and fell in love with Ohana, the mistress of his superior Ito Kihei. Ohana was pregnant with Kihei’s child, but the aging Kihei wanted to entrust her to someone else and asked Iemon to take on the responsibility. Iemon eagerly agreed but was hindered by his marriage to Oiwa. He and Kihei conspired to force Oiwa into a divorce.

Iemon started drinking heavily, abusing Oiwa, and selling off household items for his amusement. Kihei advised the heartbroken Oiwa to divorce Iemon. Manipulated by their scheme, Oiwa left home to serve a feudal retainer, and Iemon quickly married Ohana.

Meanwhile, a man named Mosuke appeared before Oiwa, revealing Iemon’s marriage to Ohana and the plot between Iemon and Kihei. Enraged, Oiwa ran off and disappeared, despite extensive searches.

Iemon and Ohana had four children and lived happily, but one summer night, Iemon started hearing Oiwa’s voice calling his name. Misfortunes followed, with their children dying mysteriously, leading Iemon to fear Oiwa’s curse. Despite repeated prayers, the curse persisted, and the Tamiya family eventually died out, as did the conspirator Kihei’s family.

One day, while repairing the roof, Iemon fell and was immobilized. Wounded, rats swarmed the pus from his ear injury, and he was placed in a rat-proof box, where he weakened and died. Since Oiwa was born in the year of the rat, it was believed that this too was her curse.

The Ghost Story of Sarayashiki

A young man heard a ghost story about “Sarayashiki” while traveling and asked an elder in the town for more details. The elder explained that the ghost of a woman named Okiku, who had drowned herself in a well, haunted the area. Okiku was rumored to appear every night to count plates. Curious, the young man decided to go see Okiku for himself.

The elder warned the young man that anyone who heard Okiku count to nine plates would die, advising him to leave after hearing her count to six. At the witching hour, Okiku began counting plates, “One plate, two plates…”

Though Okiku was a ghost, she was a strikingly beautiful woman. The young man was captivated by her beauty and returned to see her the next night and the night after that. Word of the ghostly sighting spread throughout the town, attracting more and more onlookers. Eventually, an impresario capitalized on the story, building a sideshow tent to showcase Okiku.

One night, a problem arose. The plan was to dismiss the spectators after Okiku counted to six plates, but the tent was so crowded that people couldn’t leave quickly enough. Meanwhile, Okiku continued counting, “Seven plates, eight plates…”

The spectators, remembering the tale that anyone who heard her count to nine would die, were terrified. When Okiku finally counted, “Nine plates…” everyone held their breath. However, she then continued, “Ten plates, eleven plates…” counting up to eighteen plates in total.

The stunned onlookers confronted Okiku, asking why she counted to eighteen when there were supposed to be only nine plates. Okiku replied, “Tomorrow is a day off, so I counted two days’ worth.

The Ghost Story of Botan Doro

Long ago, a shy ronin named Hagiwara Shinzaburo lived in Nezu’s Shimizutani. One day, Shinzaburo was invited by his friend Yamamoto Shijo to see the Garyubai plum trees in Kameido. On their way back, they stopped by the villa of Shijo’s acquaintance, Iijima Heizaemon. There, Shinzaburo met the beautiful young lady Otsuyu and her maid, Otsuyu. Shinzaburo fell in love with Otsuyu at first sight. As he was leaving, Otsuyu said, “If you don’t come to see me again, I will die.”

Shinzaburo was filled with a longing to see Otsuyu, but his shyness prevented him from going alone. A few months later, Shijo visited Shinzaburo and told him that Otsuyu had died of heartbreak and that Otsuyu had also died from exhaustion while nursing her.

From then on, Shinzaburo chanted Buddhist prayers for Otsuyu every day. On the night of the 13th of the Bon festival, while thinking of Otsuyu, he heard the sound of geta (wooden clogs) clacking. Looking in the direction of the sound, he saw Otsuyu and Otsuyu carrying a peony lantern. The three were overjoyed to be reunited and continued to meet every night.

One night, a man named Banzo, who worked for Shinzaburo, noticed a woman visiting Shinzaburo every night. Suspicious, Banzo peeked into Shinzaburo’s house and saw a skeletal ghost biting Shinzaburo’s neck. Horrified, Banzo consulted Hakugodo Yusai, a fortune teller who advised Shinzaburo. Yusai visited Shinzaburo’s house and declared, “You will surely die before the 20th.”

Realizing that Otsuyu was a ghost, Shinzaburo borrowed ghost-repelling talismans and an image of the Kannon Bodhisattva from a temple. Shinzaburo placed the talismans around his house, wore the Kannon image, and recited sutras. That night, as usual, Otsuyu came to visit but was unable to enter the house due to the talismans. Distressed, Otsuyu went to Banzo’s house and asked him to remove the talismans.

Initially fearful, Banzo and his wife, Omine, agreed to remove the talismans in exchange for money from Otsuyu. The next day, Banzo and Omine seized the opportunity to replace the Kannon image with a clay figure of Fudo Myo-o. That night, when Otsuyu brought the money, Banzo removed all the talismans from Shinzaburo’s house. With the talismans gone, Otsuyu joyfully entered Shinzaburo’s house.

At dawn, feeling guilty for assisting the ghost, Banzo brought Yusai and Omine to Shinzaburo’s house. They knocked on the door, but there was no answer. Fearfully entering the house, they found Shinzaburo dead with a horrifying expression, grasping at the air, and a skull biting his neck.

Summary

How was it? The boom of ghost stories and yokai (monsters) during the Edo period was a result of people seeking new stimuli amidst peace and prosperity. These ghost stories sparked imagination beyond everyday life and symbolically expressed social contradictions and anxieties. While these tales were a form of entertainment, they also resonated with people’s hearts and played a role in strengthening community bonds. The enduring popularity of ghost stories and yokai in modern times demonstrates that the themes of fear and curiosity, deeply rooted in human psychology, are universal and timeless.

In addition to ghost stories and yokai, our site features various interesting aspects of Japanese history and culture. If you are interested, we would be delighted if you read our other articles as well.

コメント