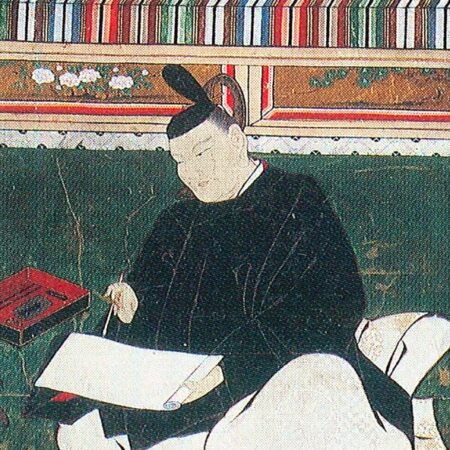

Hello everyone, have you heard of Eiichi Shibusawa? He is set to become the face of the new 10,000 yen note in July 2024, sparking interest in his legacy. However, few people are familiar with the details of his life and accomplishments. Although not extensively covered in history textbooks, Shibusawa is known as the “father of Japanese capitalism,” having been involved in the establishment of Japan’s first bank and around 500 companies throughout his life. Today, we would like to introduce you to the lesser-known story of Eiichi Shibusawa.

Who Was Eiichi Shibusawa?

Eiichi Shibusawa was an entrepreneur known as the “father of the modern Japanese economy.” Born in 1840 in Chiaraijima Village, Harisawa District, Musashi Province (now Fukaya City, Saitama Prefecture), he grew up in a farming family. From an early age, he helped with the family’s indigo dye production and sericulture, while also receiving basic education from his father. At around seven years old, he began studying the Confucian classics, including “The Analects,” under his cousin, Junchu Odaka.

In 1863, discontent with the shogunate’s class system and foreign policies, Shibusawa was influenced by the Sonnō Jōi (Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians) movement. He planned to seize Takasaki Castle and burn down foreign trading houses in Yokohama but abandoned the plan at the last moment. To escape the shogunate’s pursuit, Shibusawa left his hometown and began serving the Hitotsubashi family, where his financial and administrative skills were soon recognized. Accompanying Tokugawa Akitake, Yoshinobu’s younger brother, on a tour of Europe to observe advanced technologies, industries, and modern social systems, had a profound impact on Shibusawa’s outlook.

After returning to Japan, Shibusawa established the Shōhō Kaisho (a commercial firm) in Shizuoka, contributing to regional development. Invited by the Meiji government, he participated in the nation’s modernization efforts, including the establishment of the Tomioka Silk Mill, now a UNESCO World Heritage site. After resigning from his bureaucratic position in 1873, Shibusawa became the general supervisor (later president) of the First National Bank (now Mizuho Bank), aiming to build a modern nation through private enterprise. Throughout his life, he was involved in the establishment and nurturing of approximately 500 companies, supported around 600 public and educational institutions, and engaged in private diplomacy.

Eiichi Shibusawa was not merely focused on profit but practiced a philosophy of pursuing the public good. He believed that the nation would prosper when everyone became happier, embodying the principles he advocated. He advanced the modernization of Japan’s economy while exemplifying the ideal approach to business and society.

A Brief Timeline of Eiichi Shibusawa’s Life

Let’s take a look at the key events in Eiichi Shibusawa’s life in a brief timeline format.

| Year | Event |

| 1840 | Born in Chiaraijima (now Fukaya City, Saitama Prefecture), Japan. |

| 1847 | Studied Chinese classics under his cousin, Junchu Odaka. |

| 1863 | Planned to seize Takasaki Castle and burn down Yokohama but abandoned the plan and fled to Kyoto. |

| 1864 | Began serving Hitotsubashi Yoshinobu (later the 15th Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu). |

| 1867 | Departed for France with Tokugawa Akitake (Paris Exposition delegation). |

| 1868 | Returned from France due to the Meiji Restoration, and met with Yoshinobu in Shizuoka. |

| 1873 | Resigned from the Ministry of Finance. Opened the First National Bank and became its General Supervisor. |

| 1875 | Served as President of the First National Bank. |

| 1876 | Became the President of the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and the General Manager (later President) of the Tokyo Yōikuin (a welfare institution). |

| 1885 | Established Nippon Yūsen Kaisha (NYK Line) and served as Director. Also served as President of Tokyo Yōikuin. |

| 1901 | Oversaw the opening of Japan Women’s University and served as Financial Supervisor (later Principal). Made his Asukayama residence in Tokyo his main home. |

| 1916 | Resigned as President of the First National Bank and retired from the business world. |

| 1926 | Became an advisor when the Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya broadcasting stations merged to form the Japan Broadcasting Corporation (NHK). |

| 1931 | Passed away due to colorectal stenosis. |

Eiichi Shibusawa’s Childhood: A Glimpse of His Studious Nature and Business Acumen

Eiichi Shibusawa, originally named Ichisaburo (or Eijiro), was born on February 13, 1840, in Chiaraijima Village, Harisawa District, Musashi Province (now Fukaya City, Saitama Prefecture), which was part of the Okabe Domain’s territory of 22,250 koku under the Abe family. His father was Shiroemon Shibusawa, and his mother was Oei. Although Eiichi was the third son, he was effectively raised as the eldest son because his two older brothers had passed away at a young age.

From the age of six, Eiichi studied Confucian classics such as “The Great Learning,” “The Doctrine of the Mean,” and “The Analects” under his father’s tutelage. By the age of seven or eight, he had entered the tutelage of his cousin, Junchu Odaka, who was ten years his senior and lived in a village about seven or eight blocks away. Junchu taught him Chinese classics, including “The Elementary Learning,” “Mengqiu,” “Selections of Refined Literature,” “Zuo Zhuan,” “Records of the Grand Historian,” “Book of Han,” “Eighteen Histories,” “Tianming History,” “National History,” and “History of Japan.” Additionally, from around the age of eleven or twelve, Eiichi enjoyed reading more recreational books like “The Romance of the Three Kingdoms,” “Nansō Satomi Hakkenden,” and “The Tale of Shunkan.”

Following his father’s orders, Eiichi gradually became involved in agriculture and commerce, especially excelling in the purchase of indigo. He bought indigo not only from their own production but also from other producers, processed it into indigo cakes, and sold it to dyers in Shinano and Joshu. At the age of sixteen or seventeen, Eiichi began accompanying his grandfather Keirin to purchase indigo, honing his selection skills. He once made a bold decision to buy indigo from 21 families at once, a move that earned his father’s praise but also his strict reprimand for its boldness.

In 1854 (Ansei 1), Eiichi traveled to Edo with his uncle and returned with a wooden bookcase and inkstone case purchased for 1 ryō 2 bu. However, his father was concerned about the lavishness of these items, fearing they would undermine the family’s frugality. This incident showcased Eiichi’s early talents and ambitions, indicating that he was not destined to remain a mere farmer.

The Foiled Plan to Seize Takasaki Castle and Burn Down Yokohama, Followed by a Flight to Kyoto

Through his interactions with patriots in Edo and his admiration for Mito School teachings, Eiichi Shibusawa developed a strong anti-Tokugawa Shogunate sentiment. Along with his cousin Kisaku Shibusawa, he organized comrades aiming for an anti-foreign uprising. On November 12, 1863 (Bunkyū 3), they planned to seize Takasaki Castle to obtain weapons and ammunition, march down Kamakura Road, and set fire to Yokohama to expel foreigners.

However, at a meeting with key comrades on October 29 of the same year, Eiichi’s cousin and brother-in-law, Choshichiro Odaka, opposed the plan, citing the failure of the Tenchū Group’s uprising in Yamato as an example. Although Eiichi insisted on proceeding, the shogunate had already caught wind of the plan and was taking action. Thus, Eiichi fled to Kyoto, and the plan was never executed.

Serving Tokugawa Yoshinobu: From Anti-Shogunate Activist to Retainer

In 1864, Eiichi Shibusawa arrived in Kyoto without a clear means of livelihood. With the encouragement of Enshiro Hiraoka, a senior retainer of the Hitotsubashi family with whom he had a prior acquaintance, he began serving Hitotsubashi Yoshinobu (later the 15th Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu). This marked his transition from a farmer to a samurai.

With Hiraoka’s help, Eiichi sought an audience with Yoshinobu, candidly expressing his views while prostrating himself. He proposed that to prevent the mutual downfall of the Tokugawa and Hitotsubashi families, those aiming to overthrow the shogunate should be rallied under the Hitotsubashi family’s banner to consolidate power, eventually leading to national unification. Surprisingly, Yoshinobu agreed with this proposal.

Having gained Yoshinobu’s trust, Eiichi traveled throughout Edo and the Hitotsubashi territories, successfully recruiting soldiers to strengthen the infantry. He also addressed the Hitotsubashi family’s financial crisis by selling tribute rice as sake rice to sake dealers, generating substantial profits. Additionally, he initiated new ventures, such as selling white cotton and nitric acid, a key ingredient in gunpowder, significantly contributing to the financial recovery of the Hitotsubashi family.

As Eiichi solidified his position within the Hitotsubashi family, Yoshinobu became the 15th Shogun in 1866. Consequently, Eiichi was appointed as a retainer of the shogunate and given the role of clerk under the Army Magistrate, marking his transition from anti-shogunate activist to a key shogunate official.

Journey to Europe

In 1867, Eiichi Shibusawa accompanied Tokugawa Akitake, the younger brother of the 15th Shogun Tokugawa Yoshinobu, to the World’s Fair in Paris, France, hosted by Napoleon III. During his stay in Europe, Shibusawa cut off his topknot and adopted Western clothing. He visited a wide array of facilities and infrastructures, including parliaments, stock exchanges, banks, companies, textile factories, machine factories, hospitals, water and sewage systems, gas lighting, railways, and shipping companies. He was astonished by the advanced European civilization and the capitalist system that supported it, and he was deeply impressed by the egalitarian society without class distinctions.

Three events left a particularly strong impression on Shibusawa. First, during an audience with King Leopold II of Belgium, he was surprised to see the king himself proposing that Japan use Belgian steel, demonstrating his involvement in business. Second, he was impressed by the equal interactions between merchants, industrialists, and military personnel, devoid of any sense of hierarchy or class. Lastly, he learned about the banking system and experienced stocks and public bonds. Notably, his purchase of government bonds and railway bonds at the stock exchange, where he himself made a significant profit from railway bonds, was a major experience. This European visit had a profound impact on Shibusawa’s life.

パリから日本へ戻り静岡藩で経営の才能を発揮し、その後大蔵省へ

渋沢栄一がパリ滞在中に徳川幕府が崩壊し明治維新が起きました。渋沢栄一は日本へ戻り、徳川慶喜が引退し隠居していた静岡藩で経営の才を発揮し始めました。

当時徳川家は約400万石から70万石へと大幅に収入が減り、旧幕臣たちは生活に困窮していました。そんな中、渋沢は1869年、駿河・遠江(現在の静岡県)の豪農商からの資金と明治政府からの借金を元手に商法会所を設立し、多岐にわたる営利事業を展開しました。藩内に米穀などの日用品を供給し、茶や漆器などを藩外で販売し、さらには商品を抵当にした金融業も行いました。

そんな経営の才能をいかんなく発揮していた渋沢栄一に明治政府への出仕を勧めたのは大隈重信でした。渋沢は旧敵である新政府への移籍に抵抗しましたが、優秀な人材を徳川家に抱えておくことが捲土重来の意図として疑われることを懸念しました。勝海舟らの仲介により、徳川家の軍事エキスパートや欧米法思想の専門家が新政府に転籍していく中、最終的に渋沢も大蔵省に移りました。渋沢は当時の最高権力者である大久保利通の財政方針に異議を唱え、対等に政策論議を行うほどの実力を持っていました。その後、渋沢は民間に転じ、多くの企業を設立し、今日まで続く基盤を築きました。

Contributions of Eiichi Shibusawa to Banking and Insurance

In 1873 (Meiji 6), Eiichi Shibusawa, with the support of his direct superior in the Meiji government, Kaoru Inoue, and diplomats Alexander von Siebold and Heinrich von Siebold, convinced Mitsui Takayoshi and Ono Zenjiro (known as the Mitsui and Ono groups) to establish the “First National Bank” (later “Dai-Ichi Bank,” “Dai-Ichi Kangyo Bank,” and now “Mizuho Bank”). Shibusawa was appointed as the general supervisor.

Shibusawa played a significant role in establishing many banks, including those that would become the “three major megabanks”: Mitsubishi UFJ Bank, Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, and Mizuho Bank. He was also involved in the creation of many regional banks across Japan. In the insurance sector, Shibusawa contributed to the establishment of major insurance companies such as Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance and Nissay Dowa General Insurance.

In total, Shibusawa was involved in the founding of 47 banks and insurance companies, with their combined market value estimated at 29.16 trillion yen. The establishment of these banks marked the beginning of Shibusawa’s path as a prominent entrepreneur, eventually participating in the founding of approximately 500 companies throughout his life.

Contributions of Eiichi Shibusawa to Welfare and Healthcare

In Itabashi Ward, Tokyo, there is a large general hospital, “Tokyo Metropolitan Health and Longevity Medical Center,” which provides advanced medical care primarily to the elderly. Eiichi Shibusawa was deeply involved in the operation of its predecessor, “Yōikuin.”

Yōikuin was established to protect the socially vulnerable, including the impoverished, the sick, orphans, the elderly, and people with disabilities. It was created based on the free medical facility “Koishikawa Yōjōsho” from the Edo period. At the initial stage of Yōikuin’s establishment, Shibusawa was responsible for managing the “Seven-tenths Reserve Fund” policy, which involved saving 70% of the money saved from town expenses and using it for the relief of the poor.

Shibusawa later became involved in the administration of Yōikuin and was appointed its director in 1876 (Meiji 9). He worked tirelessly to rehabilitate the financially struggling institution. His efforts paid off, and in 1890 (Meiji 23), Yōikuin became a Tokyo municipal facility, and Shibusawa was appointed as its president.

From then on, Shibusawa continued to serve as the president of Yōikuin until his death. A statue of Eiichi Shibusawa still stands on the grounds of the Tokyo Metropolitan Health and Longevity Medical Center today, honoring his contributions.

Eiichi Shibusawa’s Contributions to Education

Eiichi Shibusawa devoted himself not only to business but also to the spread of education throughout his life. He was involved in the operation and establishment of a total of 164 educational institutions. He particularly focused on the enhancement of “commercial high schools” and “women’s education.”

At the time, graduates from prestigious national universities were considered elites. However, Shibusawa emphasized the importance of “commercial education,” which aimed to develop individuals who could actually manage businesses. To nurture the future leaders of Japan, he worked hard to establish many commercial education institutions, such as “Tokyo Commercial School” (now Hitotsubashi University), “Takachiho Commercial School” (now Takachiho University), “Okura Commercial School” (now Tokyo Keizai University), “Nagoya Commercial School,” and “Yokohama Commercial School.”

Moreover, Shibusawa was also passionate about women’s education. At that time, many women in Japan did not receive higher education, and many were illiterate. Shibusawa believed that educating women would also improve the educational level of their children.

His goal was not “women’s social advancement,” but rather to “increase the number of good wives and wise mothers who support their families.” With this in mind, he, along with Hirobumi Ito and Kaishu Katsu, established the “Society for the Promotion of Women’s Education.” Initially, the aim was to cultivate good wives and wise mothers, but later the focus shifted to creating a society where women could thrive. Shibusawa was involved in founding prestigious women’s schools such as “Japan Women’s University” and “Tokyo Jogakkan.” He continued to support these institutions throughout his life, greatly contributing to the development of women’s education.

Eiichi Shibusawa’s Contributions to Broadcasting and Communications

Eiichi Shibusawa also played a role in the history of NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation). NHK, now a public broadcasting organization under the Broadcasting Act, was initially operated as an “incorporated association.” Shibusawa served as an advisor from its inception and continued to support the broadcasting industry until his death.

Additionally, Shibusawa contributed to the creation of “Dentsu Inc.,” Japan’s largest advertising agency today, through its predecessor, “Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Company.” In July 1901, Hoshiro Mitsunaga, the founder of Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Company, established “Nippon Advertising Co., Ltd.” to raise funds for the telecommunications business. Shibusawa supported the advertising business as a sponsor. Mitsunaga later established “Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Company,” and even through various reorganizations and mergers, Shibusawa continued his support.

Furthermore, Shibusawa dedicated himself to supporting foreign communications agencies. As the head of a business delegation visiting the United States, he witnessed the scarcity of news about Japan and the prevalence of malicious reports. This motivated him to establish an “international news agency” to proactively disseminate news from Japan. Although this goal was ultimately hindered by Reuters’ influence, the “international news agency” later became the origin of “Jiji Press” and “Kyodo News,” deeply involving Shibusawa in the history of Japan’s news agencies.

Contributions of Eiichi Shibusawa to Lifelines and Beverage Manufacturers

Eiichi Shibusawa made significant contributions not only to banking, insurance, broadcasting, telecommunications, healthcare, welfare, and education but also to the growth of lifelines and beverage manufacturers.

In the electric power industry, Shibusawa was involved as a founder of “Tokyo Electric Light Company” in 1883 (the predecessor of today’s Tokyo Electric Power Company). He also played a role in the gas industry by contributing to the establishment of “Tokyo Gas Company” (now Tokyo Gas Co., Ltd.) and “Nagoya Gas Company” (now Toho Gas Co., Ltd.).

Moreover, Shibusawa was involved in the establishment of Japan’s leading beer companies, “Sapporo Beer Company” and “Asahi Beer Company.” These two companies were founded around the same time, and Shibusawa intentionally fostered competition between them to promote the development of the beer industry.

Through Shibusawa’s contributions, the infrastructure for electricity and gas was established, and beverage manufacturers grew, strengthening Japan’s industrial foundation.

Cause of Death of Eiichi Shibusawa

Eiichi Shibusawa passed away at the age of 91 due to colorectal stenosis. On October 14, a month before his death, he underwent surgery for intestinal obstruction, after which he suffered from a loss of appetite. Following the surgery, Shibusawa lay in bed, propped up with his upper body raised, and could only manage to eat a couple of spoonfuls of soup at each meal.

In his final moments, Shibusawa’s son, Atsuji Shibusawa, held one of his hands, while his grandson, Keizo Shibusawa, held the other. With both hands being held by his son and grandson, Eiichi Shibusawa peacefully passed away.

Before his death, Eiichi Shibusawa left his final words.

“Everyone, thank you for taking care of me for so long.

I had hoped to live and work until I was 100 years old, but this time, it seems I can no longer get up.

This is due to the illness, not my own failing.”

The Character of Eiichi Shibusawa

Throughout his life, Eiichi Shibusawa pursued the concept of the “unity of morality and economy.” This philosophy asserts that while businesses should seek profit, they must also be grounded in morality and hold responsibility for the prosperity of the nation and humanity as a whole. Shibusawa emphasized the importance of balancing “public good” (morality), which aims for social contribution and people’s happiness, and “profit” (economy), which is essential for the sustainability of enterprises. Although this balance is not easy to achieve, Shibusawa managed to realize it.

One reason Shibusawa was able to balance morality and economy was his “foresight.” The projects he was involved in, such as infrastructure and insurance industries that had already begun overseas but were yet to develop in Japan, were essential for people’s lives. Through his studies in Europe and interactions with various individuals, Shibusawa gathered diverse information, enabling him to identify ventures that enriched people’s lives while generating profit.

In modern Japan, globalization is advancing, and there is significant support for emerging countries. In this context, it is crucial not only to pursue profit but also to consider how it connects to the public good. In other words, leaders who emphasize both public good and profit to enrich the nation are needed.

Shibusawa was involved in establishing over 500 enterprises, but he entrusted their management to others. He desired that many people pursue “public good” rather than managing them himself. Known as the father of Japanese capitalism, Eiichi Shibusawa was a key figure in the modernization of Japan’s economy, and his numerous achievements are still highly regarded today.

Anecdotes of Eiichi Shibusawa

Let’s look at some anecdotes of Eiichi Shibusawa. Like Saigo Takamori, Shibusawa also has many interesting stories worth mentioning.

Falling into a Gutter While Reading

At the age of 12, during the New Year’s holidays, Shibusawa went out to visit relatives. While walking and reading a book, he accidentally fell into a gutter, soiling his new clothes. His mother scolded him for this. This episode shows his deep passion for learning from a young age. In later years, Shibusawa adopted the teachings of the “Analects of Confucius” as his moral compass, and his extensive vocabulary and expressive power allowed him to write works such as “The Analects and the Abacus.” These abilities were the fruits of his early dedication to study.

A Great Lover of Women

Like many historical figures, Shibusawa was known to be quite a lover of women. In 1863, the same year his first daughter was born, Shibusawa received 100 ryō from his father and headed to Kyoto with his cousin Kisaku Shibusawa. During this time, he visited Yoshiwara for the first time and later recounted, “I quickly spent 24 or 25 ryō.” Considering that one ryō was worth approximately 130,000 yen at that time, Shibusawa spent about 3.25 million yen in Yoshiwara.

Shibusawa was known to have at least 20 illegitimate children. However, this was not unusual for the time, as many men around him also enjoyed such activities. For instance, Hirobumi Ito was known for even more flamboyant affairs, and Yoshinobu Tokugawa fathered ten sons and eleven daughters with his concubines.

Shibusawa’s wife must have had a tough time with his behavior. His second wife, Kaneko Shibusawa, once told their children, “Your father found something tasty in the ‘Analects.’ If it had been the Bible, he wouldn’t have kept to it,” referring to the Bible’s strict moral teachings, which include “Thou shalt not commit adultery,” whereas the “Analects” did not emphasize sexual morality.

A Falling Out with Yataro Iwasaki

Another prominent businessman who flourished in the same era as Eiichi Shibusawa was Yataro Iwasaki. Often compared to Shibusawa, Iwasaki held a fundamentally opposite philosophy.

In 1878, Iwasaki called Shibusawa to a boat house called Kashiwaya in Mukojima. Over drinks, he asked Shibusawa, “What should the future of business look like?” Iwasaki aimed to monopolize the shipping industry and wanted to bring Shibusawa into his fold.

However, Shibusawa expounded on his belief in joint-stock partnerships (gohonshugi) to Iwasaki. Iwasaki disagreed vehemently, leading to a heated debate. Ultimately, their opinions remained irreconcilable, and Shibusawa left the meeting. This incident caused a rift between the two, and their relationship became strained.

Reasons for Eiichi Shibusawa Being Chosen for the New 10,000 Yen Note

Eiichi Shibusawa was chosen as the face of the new 10,000 yen note due to his significant contributions as the “father of Japanese capitalism,” supporting the establishment of numerous companies without pursuing personal gain. He was involved in the establishment of about 500 companies, many of which have grown into major corporations driving Japan’s economy today. Additionally, Shibusawa contributed to approximately 600 social welfare and charitable activities.

Without Shibusawa, Japanese capitalism might have lagged behind Western countries. Despite his great contributions, he never named any company after himself, demonstrating his selfless dedication to advancing Japanese capitalism. Thus, Eiichi Shibusawa is a fitting choice for the face of the currency.

In 1963 (Showa 38), Shibusawa was a finalist for the 1,000 yen note, but Hirobumi Ito was chosen instead. At that time, portraits of men with beards were preferred for anti-counterfeiting reasons, as intricately drawn beards were considered effective in preventing forgery.

However, with advancements in anti-counterfeiting technology, portraits of clean-shaven men and women have become viable options. As a result, Eiichi Shibusawa was selected for the new 10,000 yen note.

Was Eiichi Shibusawa Already Featured on Currency in the Meiji Era?

Eiichi Shibusawa is set to be featured on the 10,000 yen note in 2024. However, his portrait had already been used on foreign currency during the Meiji era. How did this come about?

In 1911, Japan established the Residency-General in Korea and stripped the Korean Empire of its diplomatic rights, effectively making it a protectorate. Japan then withdrew the Korean currencies “Yeopjeon” and “Baekdonghwa” from circulation, replacing them with Japanese “First Bank Notes.”

Shibusawa, along with the Mitsui and Ono groups, founded Japan’s first bank, the First National Bank, in 1873. Renamed the “First Bank” in 1896, it expanded its operations to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and the Korean Empire. During this time, the First Bank notes issued in Korea featured Shibusawa’s portrait, as he was the bank’s president. Remarkably, his portrait appeared on three denominations: 1 yen, 5 yen, and 10 yen. Truly the father of Japanese banking, Shibusawa had already been the face of currency over a century ago.

Eiichi Shibusawa Created the Luxurious Ginza District

Today, Ginza is globally renowned as a luxurious district where celebrities gather. However, this image was actually cultivated through the efforts of Eiichi Shibusawa.

In 1872, a massive fire turned Ginza into a wasteland. Shibusawa and Kaoru Inoue quickly devised a reconstruction plan. Foreseeing economic development, they widened the streets to facilitate smoother movement of people and goods.

Moreover, with the assistance of foreign countries, they increased Western-style architecture, transforming Ginza into a modern and sophisticated town. Thus, Ginza was reborn as a glamorous high-end district thanks to Eiichi Shibusawa’s vision and efforts.

Summary

How was it? This time, we looked at Eiichi Shibusawa. From a young age, he was not only proficient in academics but also well-versed in business. As an entrepreneur, he was involved in the establishment of various companies, significantly contributing to Japan’s economic growth. However, he believed in pursuing both profit and morality, a mindset from which we can still learn much today.

On this site, we introduce various other fascinating aspects of Japanese history and culture besides Eiichi Shibusawa. If you are interested, we would be delighted if you read our other articles as well!

コメント