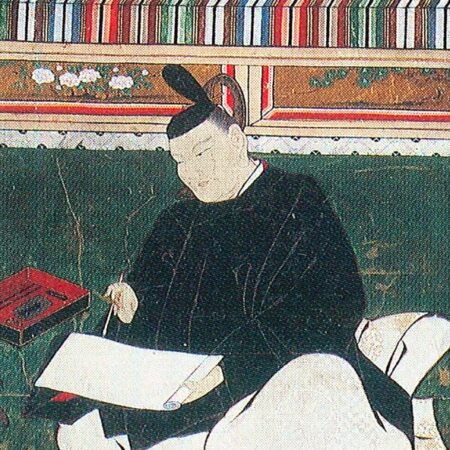

Do you know about Katsu Kaishū? During the late Edo period, he was a samurai, and in the Meiji era, he played a significant role as a politician in advancing Japan’s modernization. He was also the first Japanese person to accomplish the great feat of crossing the Pacific Ocean. In today’s increasingly globalized world, having an international perspective and awareness is essential. Katsu Kaishū was a person who, from the late Edo period to the Meiji era, always looked ahead to the future and acted boldly. His innovative thinking and decisive actions shaped history, bringing an end to the 260-year-long Tokugawa shogunate despite being a retainer of the shogunate himself. This time, we will take a closer look at such a remarkable figure, Katsu Kaishū.

Who was Katsu Kaishū?

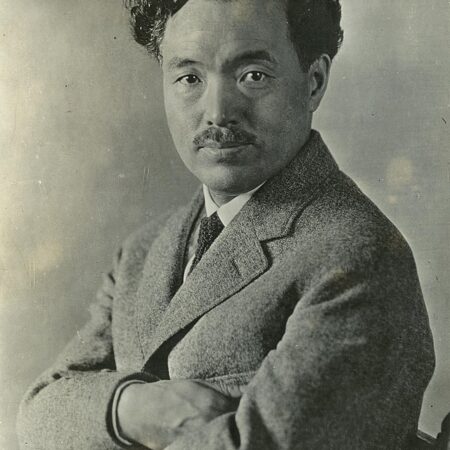

Katsu Kaishū was a samurai and politician who dedicated himself to the modernization of Japan from the late Edo period to the Meiji era. Born in 1823 into a samurai family in Edo (now Tokyo), he excelled in swordsmanship and Dutch studies from a young age. In Nagasaki, he studied the latest academic fields and navigation techniques, and he worked to disseminate this knowledge. In 1860, he traveled to the United States aboard the steam warship Kanrin Maru, and after returning to Japan, he established a naval school in Kobe, contributing to the development of the navy and laying the foundations of a modern nation.

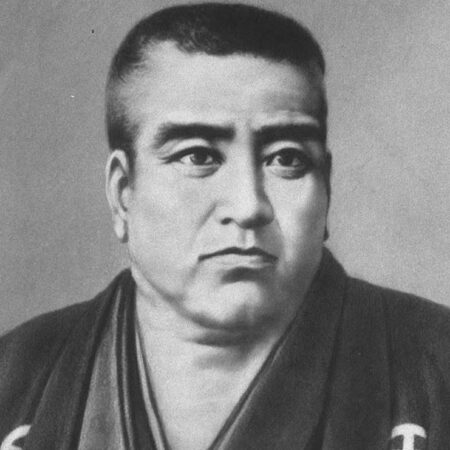

When the Boshin War broke out, Katsu Kaishū negotiated with Saigō Takamori, successfully arranging the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle without bloodshed, thus saving the city of Edo from the ravages of war. This bloodless surrender of Edo Castle highlights his exceptional negotiation skills and strong commitment to peace.

After the Meiji Restoration, Katsu Kaishū held various important positions such as Sangi (councilor), Navy Minister, and Privy Councilor, and he was appointed as a Count. He was known not only as a politician but also as a talented literary figure, excelling in waka (Japanese poetry) and Chinese poetry.

Katsu Kaishū’s achievements lie in his efforts to advance Japan’s modernization and his continual pursuit of peaceful solutions to avoid civil war. His life and accomplishments demonstrate the importance of making calm and rational decisions and taking actions that consider the nation’s future, even in turbulent times. Katsu Kaishū is a remarkable figure whose name should be eternally engraved in Japanese history, and there is much to learn from his life.

A Brief Timeline of Katsu Kaishū’s Life

Let’s take a look at the key events in Katsu Kaishū’s life in a brief timeline format:

| Year | Event |

| 1823 | Born as the eldest son of Katsu Kokichi in Honjo, Edo (now Sumida Ward, Tokyo). His childhood name was “Rintarō.” |

| 1829 | Summoned to Edo Castle as a playmate for Hatsunosuke, the grandson of the 11th Shogun Tokugawa Ienari. |

| 1838 | Inherited the headship of the Katsu family after his father retired. |

| 1850 | Traveled to the United States aboard the steam warship Kanrin Maru. |

| 1854 | Submitted a proposal on coastal defense. Recognized for his talents, he was appointed as an inspector for coastal defense by the Edo Shogunate. |

| 1860 | As the captain of the Kanrin Maru, he crossed the Pacific Ocean and arrived in San Francisco, USA, becoming the first Japanese to accomplish a trans-Pacific voyage. |

| 1862 | Met Sakamoto Ryōma, who later became his disciple. |

| 1864 | Established the Kobe Naval Training Center and was appointed as Naval Commissioner. |

| 1866 | Achieved a ceasefire in the Second Chōshū Expedition. |

| 1868 | The Boshin War began with the Battle of Toba-Fushimi in January. Later, he negotiated with Saigō Takamori and realized the peaceful surrender of Edo Castle, averting a large-scale battle. |

| 1872 | Appointed as Vice Minister of the Navy and later as Navy Minister. |

| 1873 | Appointed as Councillor and Navy Minister. |

| 1899 | Passed away due to a cerebral hemorrhage. |

Childhood Learning Dutch Studies and Swordsmanship

In 1823 (Bunsei 6), Katsu Kaishū was born into a hatamoto family with an annual stipend of about 41 koku. His childhood name and common name were “Rintarō,” his real name was “Yoshikuni,” and after the Meiji Restoration, he changed his name to “Yasuyoshi.” “Kaishū” was his pseudonym.

As a teenager, Katsu Kaishū learned swordsmanship and Zen from the swordsman “Shimada Toranosuke.” His talent and efforts were exceptional, and he eventually served as an assistant instructor under his master. He received full certification in the Jikishinkage-ryū style. Under his master’s guidance, he not only mastered swordsmanship but also cultivated his spiritual discipline.

At his master’s recommendation, Kaishū pursued Western military studies and became a disciple of the Dutch scholar “Nagai Seigai,” learning Dutch studies. His dedication was immense; he borrowed a rare Dutch-Japanese dictionary, “Doef-Halma,” and painstakingly copied it out by hand twice over a year—once for personal use and once for sale. This effort showcased his seriousness and perseverance in his studies.

In 1850 (Kaei 3), Kaishū opened a private school, “Hyōkaijuku,” teaching Dutch studies and military tactics. This school became a place where he imparted his acquired knowledge and skills to others, marking an important step towards Japan’s modernization. Katsu Kaishū’s childhood was characterized by a deep curiosity and commitment to swordsmanship and Dutch studies, laying the foundation for his life’s work.

From Submitting Proposals to the Shogunate to Achieving the First Trans-Pacific Voyage by a Japanese

In 1850, at the age of 27, Katsu Kaishū opened a Dutch studies school. After Commodore Perry’s arrival in 1853, Kaishū was shocked and submitted a proposal to the Shogunate, suggesting the recruitment of talented individuals regardless of status and the construction of warships. This proposal caught the attention of the Shogunate, and at the age of 31, Kaishū was appointed as an inspector for coastal defense.

The following year, Kaishū began studying at the Naval Training Center in Nagasaki, absorbing the latest naval technology and knowledge. This significantly enhanced his military expertise and leadership skills.

In 1860, at the age of 37, Kaishū was appointed captain of the Kanrin Maru and undertook Japan’s first trans-Pacific voyage to San Francisco as part of a delegation to conclude the Treaty of Amity and Commerce between Japan and the United States. This successful voyage demonstrated his leadership and navigational skills.

After witnessing America’s modernization firsthand, Kaishū was promoted to Naval Commissioner upon his return and worked to establish the navy within the crumbling Shogunate. He founded a new Naval Training Center, which educated not only Shogunate retainers but also anti-foreignist ronin, including Sakamoto Ryōma.

Despite being dismissed the following year due to political issues, Kaishū’s interactions with key figures like Kido Takayoshi and Saigō Takamori had a significant impact. His efforts in education and diplomacy were crucial steps toward Japan’s modernization and national defense, leaving a lasting influence on Japanese history.

Meeting Sakamoto Ryōma

Upon returning from America, Katsu Kaishū met Sakamoto Ryōma, a notable samurai of the Bakumatsu period, on December 9, 1862. Ryōma visited Kaishū’s residence with an introduction letter from Matsudaira Shungaku, the Shogunate’s political chief.

At first, Ryōma, an anti-foreignist, was skeptical of Kaishū, who supported opening Japan to the world. However, after listening to Kaishū’s arguments for strengthening Japan’s defense and national power through trade with foreign countries, Ryōma was convinced and decided to become Kaishū’s disciple.

This encounter broadened Ryōma’s perspective and significantly influenced his subsequent activities. He proudly reported his decision to become Kaishū’s disciple to his sister in two letters, showing deep respect for Kaishū.

Achieving a Ceasefire in the Second Chōshū Expedition

In 1866 (Keiō 2), Katsu Kaishū was reappointed and took action to achieve a ceasefire in the “Second Chōshū Expedition.” This conflict arose when the Shogunate’s forces attacked Chōshū Domain, which had become a leader of the sonnō jōi (revere the emperor, expel the barbarians) movement. The conflict started with the Kinmon Incident (Hamaguri Rebellion), where Chōshū forces fired on the Imperial Palace in Kyoto.

Kaishū negotiated with Chōshū leaders Hirozawa Masami and Inoue Kaoru in Miyajima, Hiroshima Prefecture, paving the way for a ceasefire agreement. This agreement marked the Shogunate’s failure in the expedition and highlighted the Shogunate’s decline.

Kaishū’s negotiation skills and calm judgment during turbulent times had a profound impact on Japanese history, avoiding unnecessary warfare and achieving a significant ceasefire agreement during the Bakumatsu period.

Katsu Kaishū after the Meiji Restoration

After the Meiji Restoration, Katsu Kaishū served in important positions such as Deputy Minister of the Navy, Navy Minister, and Councillor, and was ennobled as a Count. During the Satsuma Rebellion in 1877 (Meiji 10), he sympathized with Saigō Takamori and worked to restore his honor.

Even after retiring from politics, Kaishū remained an influential advisor, overseeing the care of the retired Tokugawa Yoshinobu. He also promoted tea cultivation in Shizuoka’s Sunpu as employment for displaced samurai, contributing to Shizuoka’s reputation as a tea-producing region.

In 1888, Kaishū was appointed as a Privy Councilor, actively advising the government. He opposed the invasion of Korea and was critical of the Sino-Japanese War. In his later years, he wrote several works on Japanese history, including “Fukijinroku” and histories of the navy and army.

The Death of Katsu Kaishū

On January 19, 1899, Katsu Kaishū collapsed after a bath. After asking for ginger tea, he drank brandy and fell unconscious, passing away from a cerebral hemorrhage at the age of 77. His last words were, “This is the end.”

Katsu Kaishū devoted his life to the Tokugawa family and did not regret his actions. He often remarked that death would be like waking from a dream, and his last words reflected a sense of fulfillment and release. His life and contributions continue to be remembered as crucial to Japan’s modernization.

The Personality of Katsu Kaishū

Katsu Kaishū was a person with a remarkably progressive and global perspective for his time. Even during Japan’s period of isolation, he was convinced that the future would belong to English and Dutch studies, and he pursued both languages diligently. Witnessing Perry’s arrival firsthand, he advocated for modernization to the Shogunate, and he personally experienced America’s modernization by crossing the Pacific Ocean as a ship captain. He constantly challenged conventional wisdom and embraced new ideas.

Despite the fall of the Shogunate, Kaishū continued to care for the Tokugawa family and worked to restore the honor of Saigō Takamori, who had opposed the Meiji government. This demonstrates his deep sense of compassion and humanity.

However, in his private life, Kaishū had a temper and could be short-tempered. It is said that when he was in a bad mood, he would sometimes expel his family from the house or ignore visitors. Thus, Katsu Kaishū was a person with a progressive and global outlook, combined with a strong sense of humanity and very human emotions.

Episodes from the Life of Katsu Kaishū

Let’s take a look at some of the various fascinating episodes from Katsu Kaishū’s life. He has many notable stories worth sharing!

Katsu Kaishū’s Father was in Confinement When He Was Born

Katsu Kaishū’s father, Katsu Kokichi, was a delinquent hatamoto who never held any official position and spent his time fighting and frequenting the pleasure district of Yoshiwara. At 21, Kokichi ran away and hid in Shizuoka, but he was brought back by his relative, Otokoya Seichirō, and confined in a room in their home. Kokichi remained in this confinement until Kaishū (then called Rintarō) was three years old and did not witness his son’s birth.

Bitten by a Dog in His Childhood

Katsu Kaishū,

born into a poor samurai family, rose through the ranks to become a key figure in the Shogunate and was instrumental in achieving the bloodless surrender of Edo Castle during the Boshin War. However, he experienced a tragic incident in his childhood.

At the age of nine, while practicing in the neighborhood, Kaishū was bitten by a sick dog on his testicles. According to his father’s record, “Yume Suigoku,” when they examined him, his testicles were missing. When asked if his life could be saved, the doctor replied that it would be difficult.

Despite the unimaginable pain and suffering, Kaishū recovered completely after 70 days. Later, he had one legitimate wife, five concubines, and fathered nine children, indicating that his testicles were indeed intact. However, this traumatic childhood incident left him with a lasting fear of dogs.

Living in the Inner Chambers of Edo Castle at Age Seven

At the age of seven, Kaishū visited the gardens of Edo Castle. His behavior caught the attention of the officials, and he was recruited as a companion for Hatsunosuke, the grandson of the then-Shogun Tokugawa Ienari. Thus, Kaishū spent two years living in the Inner Chambers of Edo Castle.

Kaishū, known for his mischievous behavior, was often scolded by the maidservants. However, this experience proved valuable later in life. When wasteful spending in the Inner Chambers became an issue, Kaishū went to the Inner Chambers and, by allowing the maidservants to indulge in luxury, successfully encouraged them to practice voluntary frugality. This early experience taught him valuable lessons that he later applied in his career.

A Forced Sea Voyage Leading to Shipwreck

At the age of 33, Kaishū entered the Naval Training Center in Nagasaki, where he studied Dutch, mathematics, navigation, and shipbuilding. In the autumn of 1857, at the age of 35, he decided to undertake a long-distance sea voyage on the newly completed kotter ship. Despite being warned by his Dutch naval instructor, Kattendyke, about bad weather, Kaishū proceeded with the voyage, reaching the Goto Islands.

As predicted, the weather worsened, the ship was damaged, and it nearly sank after a hole appeared in the bottom. Nevertheless, they managed to stabilize the ship and return the next day. Reflecting on the incident, Kaishū recounted that Kattendyke laughed and said it was a good experience, impressing Kaishū with his broad-mindedness.

Pretending to Be Well to Achieve the First Trans-Pacific Voyage by a Japanese

In 1860, at the age of 38, Kaishū embarked on the Kanrin Maru to head to San Francisco. On the day of departure, he was bedridden with a high fever and severe headache. However, he believed it was better to die on a warship than on a tatami mat, so he told his wife he was just going to Shinagawa and then left for San Francisco. By the time they arrived, he had fully recovered.

Although there’s a story that the Kanrin Maru was crewed solely by Japanese, in reality, they were accompanied by Lieutenant Brooke of the American Navy, who was returning to the United States after being shipwrecked in Uraga, along with American sailors who assisted them. Lieutenant Brooke noted that Kaishū was frequently seasick. This episode illustrates Kaishū’s boldness and adventurous spirit.

Angering Officials with His Honest Report on America

After returning from San Francisco, Kaishū was asked by senior Shogunate officials if he had encountered anything unusual in the foreign land. He replied, “Human behavior is the same throughout history and across the world. There was nothing particularly unusual in America.”

When pressed further, Kaishū explained, “In America, both in government and civilian life, those in positions of power are intelligent. This is the only significant difference from our country.” This statement angered his superiors, as it highlighted the merit-based system in America compared to the hereditary and status-based system in Japan, and was seen as a harsh critique of the Japanese system.

These episodes highlight Katsu Kaishū’s progressive, bold, and compassionate nature, as well as his willingness to challenge conventional norms and embrace new experiences, leaving a lasting impact on Japanese history.

Katsu Kaishū’s Compassion Leading to Shizuoka Becoming a Major Tea-Producing Region

During the Meiji Restoration, there were two retainers of the former Shogunate, Okusa Takijirō and Chūjō Kanesuke. They, along with many other retainers, planned to commit seppuku (ritual suicide) at Edo Castle. However, Katsu Kaishū persuaded them, saying, “If you commit seppuku now, it will be a meaningless death. Go live quietly in Shizuoka.” Convinced by his words, they abandoned their plans for seppuku.

A few years later, the two men consulted Kaishū, saying, “There is neglected land in a place called Kanaya, and we want to cultivate it.” Kaishū praised their initiative and continued to provide support to them and their fellow former retainers. Eventually, they planted tea on the cultivated land and started trading the tea leaves in Yokohama. This marked the beginning of Shizuoka tea.

Without Katsu Kaishū’s support for Okusa and Chūjō, Shizuoka might never have become the renowned tea-producing region it is today. His compassion and assistance were pivotal in this development.

A Wife Refusing to be Buried in the Same Grave Due to Her Husband’s Womanizing

Katsu Kaishū, who was prominent on the public stage, had a tumultuous history with women. While at the Nagasaki Naval Training Center, he fathered a son with a woman he met there and had daughters with various maidservants. His legitimate wife, Tami, was perpetually discontent with this situation. Katsu Kaishū attempted to placate Tami by saying, “The fact that there are no conflicts in the house despite my relationships with other women is a testament to how great my wife is,” but such comments did little to satisfy her.

As Tami lay on her deathbed, her final wish was extraordinary for the time: “I want to be buried in a separate grave from my husband. Please lay me to rest in the same cemetery as our prematurely deceased son, Kojika.” During an era when it was customary for a wife to be buried in her husband’s grave, she made this request, indicating how deeply she suffered from her husband’s unfaithfulness.

However, ten years later, Tami’s grave was placed next to Katsu Kaishū’s with the sentiment, “It’s fine now.”

Summary

How was it? This time, we looked at who Katsu Kaishū was through a simple timeline, his personality, and various episodes. From the era of national isolation, Katsu Kaishū had a forward-thinking mindset, feeling a sense of crisis about Japan’s delayed modernization and looking towards the world. His thoughts and efforts are something we should learn from even today.

This website also introduces interesting aspects of Japanese history and culture beyond Katsu Kaishū. If you are interested, we would be delighted if you read our other articles as well!

コメント