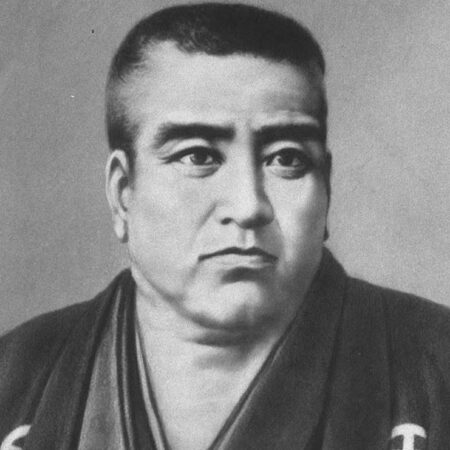

Everyone, how much do you know about Tokugawa Ieyasu? He is quite famous in Japanese history for winning the Battle of Sekigahara and founding the Edo Shogunate. However, did you know that he spent his early years as a hostage? It’s surprising to learn that a man who would eventually unify the country and establish a shogunate was once a hostage. Moreover, there’s even an embarrassing anecdote about him allegedly soiling himself out of fear during a battle. This time, we’ll introduce some lesser-known facts about Tokugawa Ieyasu.

What Did Tokugawa Ieyasu Achieve?

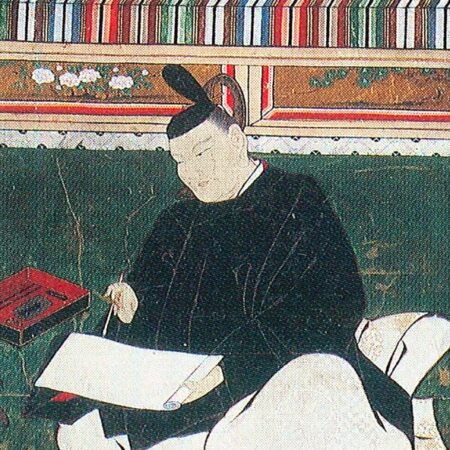

Tokugawa Ieyasu is known as the great unifier who brought an end to the Sengoku period. Alongside Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he is one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history. His life began as a hostage in a turbulent period and, through skillful politics and strategy, he reshaped Japan’s history.

As a child hostage of the Oda clan, Ieyasu quickly learned to navigate the harsh political environment. His alliance with Oda Nobunaga and his patient actions under Toyotomi Hideyoshi demonstrate his ability to discern the right time and place to act. After Hideyoshi’s death, Ieyasu achieved the unification of Japan by winning the Battle of Sekigahara.

In 1603, Ieyasu was appointed Shogun and established the shogunate in Edo, inaugurating the Edo period, which lasted about 260 years. This era was marked by political stability and cultural development, maintained under the firm governance of the Tokugawa shogunate.

One of Ieyasu’s famous sayings is, “If the cuckoo does not sing, make it sing,” reflecting his proactive and positive attitude, emphasizing the importance of taking action. Anecdotes about him reveal a calm, composed leader with excellent situational judgment and respect for his enemies. His magnanimity, particularly during hostage exchanges, earned him great respect from his contemporaries.

Tokugawa Ieyasu was not just a warlord but a visionary who implemented policies for Japan’s future, laying the foundation for long-term peace and prosperity. His rule strengthened Japan’s centralized political system and paved the way for an economic and cultural golden age.

A Timeline of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Life

Let’s now look at the specifics of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s life in a timeline format.

| Year | Event |

| 1543 | Born in Mikawa Province |

| 1547 | Taken hostage by the Oda and Imagawa clans |

| 1560 | Gains independence after the Battle of Okehazama |

| 1562 | Forms an alliance with Oda Nobunaga |

| 1582 | Incident at Honnoji; the Iga Escape |

| 1600 | Victory at the Battle of Sekigahara |

| 1603 | Becomes Shogun and establishes the Edo Shogunate |

| 1615 | Destroys the Toyotomi clan |

| 1616 | Dies of illness at Sunpu Castle |

1547: Taken Hostage by the Oda and Imagawa Clans

The life of Tokugawa Ieyasu began in the Matsudaira family of Mikawa Province, where he was known by his childhood name “Takechiyo.” When Takechiyo was just six years old, his father, Matsudaira Hirotada, was defeated by Oda Nobuhide (the father of Oda Nobunaga) of Owari Province. As a result, Takechiyo was sent as a hostage to the Oda clan. For a young child, being separated from his family must have been an immense pain. Then, only two years later, in 1549, Takechiyo suffered another blow: his father Hirotada passed away. There are various theories about Hirotada’s death, including illness or assassination by a subordinate, but regardless of the cause, young Takechiyo became the head of the Matsudaira family, bearing an enormous burden.

Fate continued to test him. Imagawa Yoshimoto attacked the Oda clan under the pretext of saving the Matsudaira family, resulting in Takechiyo being sent as a hostage to the Imagawa clan. Under the protection of the Imagawa family, Takechiyo spent his formative years at Sunpu Castle. At the age of 14, he underwent his coming-of-age ceremony and was given the name “Matsudaira Motonobu” (later changed to “Matsudaira Motoyasu”) by Imagawa Yoshimoto, incorporating the character “元” (moto) from Yoshimoto’s name. This marked his recognition as an adult and the beginning of his new life as a warrior.

1560: The Battle of Okehazama

In May 1560, a significant turning point in the Sengoku period occurred. Imagawa Yoshimoto led a formidable army of 25,000 troops to invade Owari Province, resulting in the Battle of Okehazama. During this battle, Yoshimoto was killed by Oda Nobunaga’s surprise attack.

At that time, Tokugawa Ieyasu, then known as Matsudaira Motoyasu, was with the Imagawa clan at Odaka Castle, where he successfully delivered provisions. The news of Yoshimoto’s death was brought to him by his uncle. After confirming the information, Motoyasu left Odaka Castle and headed for Okazaki Castle. With the Imagawa forces retreating to Suruga and abandoning Okazaki Castle, Motoyasu returned to the castle after 11 years. From this stronghold, he reunited the Matsudaira clan and his retainers, bringing western Mikawa under his control.

After Yoshimoto’s death, Motoyasu continued to fight for the Imagawa clan for a while and is said to have suggested a punitive expedition to mourn Yoshimoto’s death to his heir, Ujizane. However, by 1561 (Eiroku 4), he had given up on Ujizane and successfully negotiated an alliance with Oda Nobunaga.

The Battle of Okehazama was not just a military victory for Tokugawa Ieyasu but also an excellent opportunity for political independence and territorial expansion. This event was a crucial step in establishing his status as a Sengoku daimyo and laying the foundation for his future unification of Japan.

1582: The Iga Escape Following the Incident at Honnoji

In June 1582, Japan was undergoing a significant transformation during the Sengoku period. This was when Oda Nobunaga was killed by Akechi Mitsuhide at Honnoji Temple in Kyoto, an event known as the Incident at Honnoji, which shocked many Sengoku daimyos. Tokugawa Ieyasu was no exception and heard the news while in Sakai, Izumi Province. Ieyasu was touring the Kinai region at Nobunaga’s invitation, accompanied by only about 30 retainers, a very small number.

Ieyasu and his small group debated whether to join the battle in Kyoto, but they decided it was too reckless with their limited numbers. They quickly decided to return to their home province of Mikawa. To choose the shortest and safest route, they opted for the Iga route. This route took them from Sakai through southern Yamashiro, then via Shigaraki in Omi, through Iga Marubashira, over the Suzuka Mountains, and into Ise Province.

This journey was extremely challenging. There were fears of uprisings by local samurai and farmers, and they were indeed attacked by them along the way. In this dangerous situation, the presence of Hattori Hanzo, a ninja from Iga, played a significant role. Hanzo gathered local Koga and Iga warriors to protect Ieyasu’s party and help them escape to Ise. This experience led Ieyasu to later employ the ninja organizations of Koga and Iga.

After arriving in Ise, there are various theories about how Ieyasu crossed to Mikawa, but he safely arrived in Mikawa on June 4, two days after leaving Sakai. The “Iga Escape” was more than just a journey for Tokugawa Ieyasu; it was one of the three major crises in his life.

1600: Victory at the Battle of Sekigahara

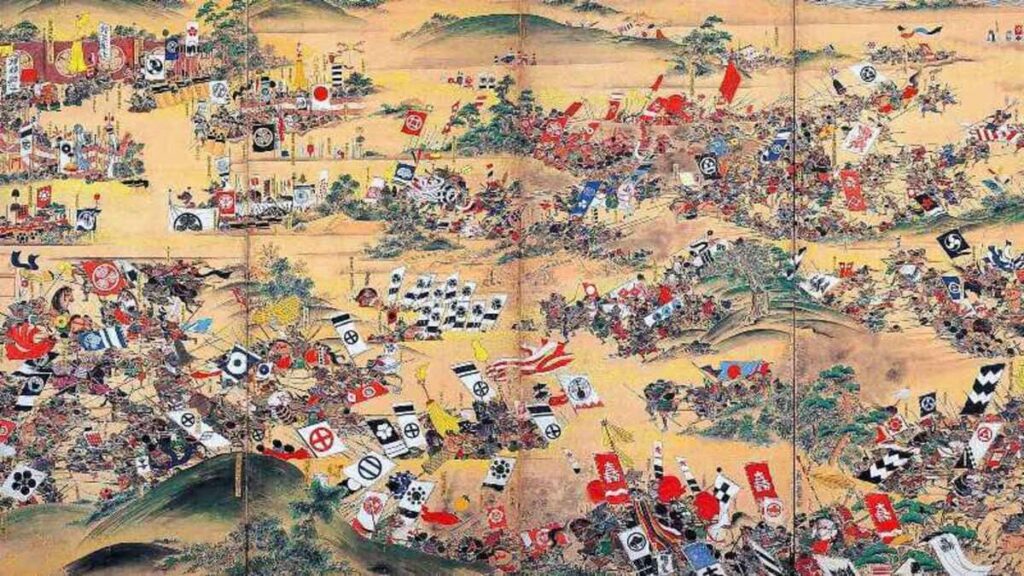

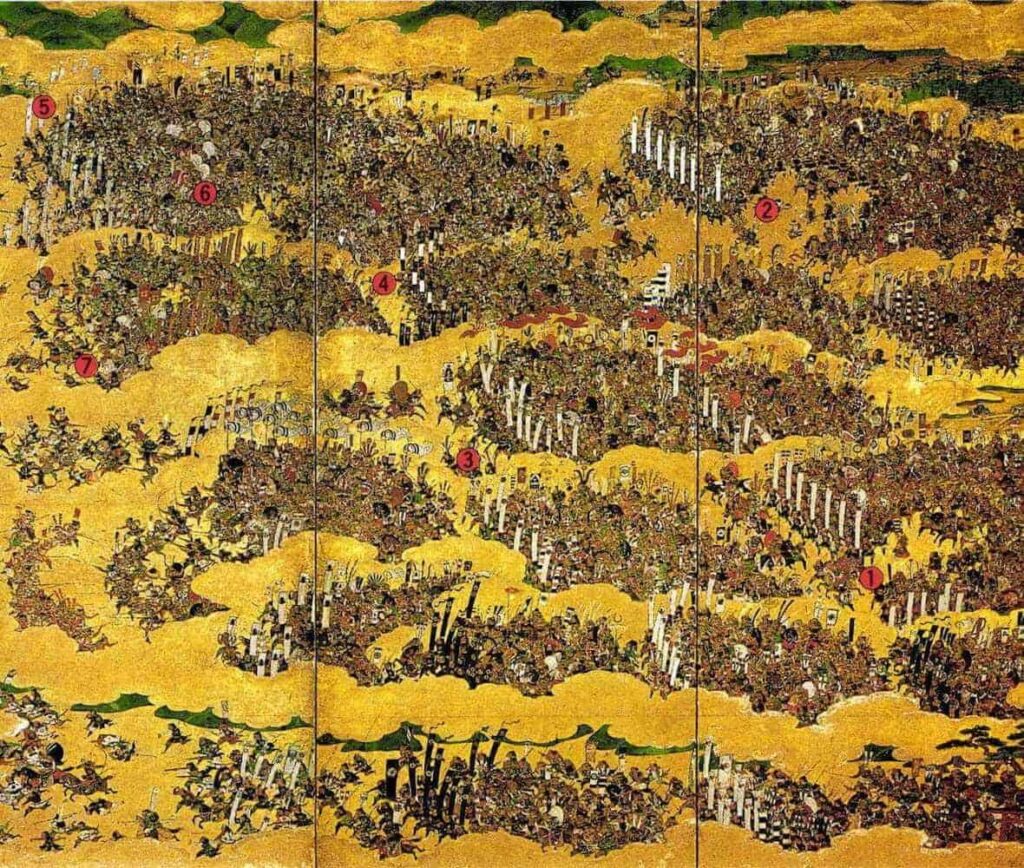

In 1600, a pivotal battle in Japanese history took place at Sekigahara. This battle occurred amidst the power vacuum and intensified conflicts among daimyos following the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The confrontation between the Eastern Army, led by Tokugawa Ieyasu, and the Western Army, led by Ishida Mitsunari, would determine the fate of all Japan.

After Hideyoshi’s death, a system of five elders and five magistrates was established to uphold his legacy and maintain some stability. However, Ieyasu’s actions, which ignored Hideyoshi’s will, gradually stirred discontent among other daimyos. Particularly, Ishida Mitsunari opposed Ieyasu’s behavior, and their rivalry deepened. Ieyasu’s unilateral decisions regarding marriages and land exchanges among daimyos, which went against Toyotomi policies, increasingly bolstered his power.

Tensions between Ieyasu and Mitsunari escalated, leading Mitsunari to take action to curb Ieyasu’s autonomy. After Mitsunari raised an army, Ieyasu quickly returned east, rallying the daimyos to confront Mitsunari. This confrontation ultimately led to a full-scale war at Sekigahara.

The Battle of Sekigahara saw approximately 160,000 troops from the Western and Eastern armies clash, with the conflict being resolved in an astonishingly swift six hours. Initially, the Western Army held the advantage, but the tide turned significantly due to the betrayal of Kobayakawa Hideaki, who defected to the Eastern Army. His actions gave a decisive boost to the Eastern Army, drastically changing the course of the battle.

Ieyasu’s strategy of enticing Western daimyos with promises of rewards also proved effective, leading to a series of defections. Ultimately, the Eastern Army achieved a decisive victory. As a result of this battle, Tokugawa Ieyasu became the de facto ruler of Japan and successfully laid the foundation for the Edo Shogunate.

1615: The Summer and Winter Sieges of Osaka and the Fall of the Toyotomi Clan

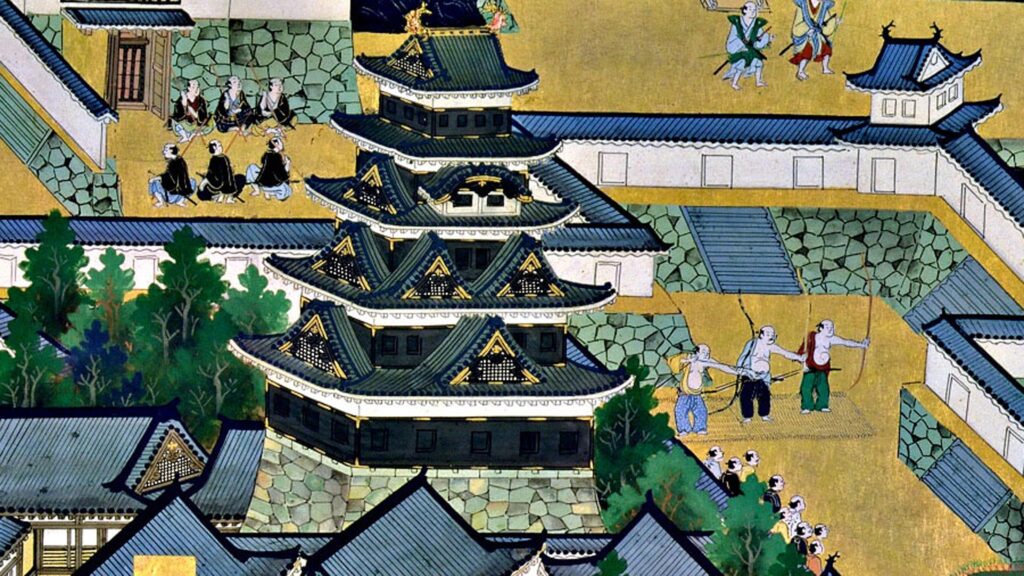

In 1603, Japan entered a new era as Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed Shogun and declared the establishment of the Edo Shogunate. This historic event marked the beginning of a new phase in which the Tokugawa family would lead Japan’s political landscape following their victory at the Battle of Sekigahara.

The title of Shogun was the highest rank a samurai could attain, and being appointed to this position by the Emperor conferred absolute authority. Ieyasu’s appointment not only granted him an honorable position but also demonstrated to the nation that he and the Tokugawa family stood at the pinnacle of the samurai hierarchy.

After the overwhelming victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, Ieyasu effectively absorbed the authority previously held by the Toyotomi regime. This move successfully weakened the influence of former Toyotomi loyalists, including Toyotomi Hideyori and his key retainers, further solidifying the Tokugawa family’s power base. In 1603 (Keichō 8), Ieyasu was officially appointed as Shogun, establishing his position firmly.

By establishing the hereditary system of the Shogunate, Ieyasu laid the foundation for the Tokugawa family to reign as the leaders of Japan’s samurai for generations to come. This ensured the Tokugawa family’s absolute dominance and sent a clear message to other daimyo and samurai.

The birth of the new shogunate centered in Edo brought significant changes to Japan’s political structure. The Edo Shogunate went on to govern Japan for approximately 260 years, during which Edo (now Tokyo) flourished as the political and cultural center of the nation.

1615年 大阪夏の陣・冬の陣で豊臣氏を滅ぼす

Three years after his victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, Tokugawa Ieyasu was appointed as Shogun in 1603, becoming the de facto ruler of Japan. However, in Osaka, Toyotomi Hideyori, the son of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and his mother Yodo-dono still wielded considerable influence. The presence of Hideyori was a potential threat to Ieyasu, and resolving this was essential for Ieyasu’s consolidation of power.

Ieyasu first rewarded the daimyo who supported him at the Battle of Sekigahara, gradually eroding the loyalty towards the Toyotomi clan. Additionally, as a political strategy, he arranged for his granddaughter Senhime to marry Toyotomi Hideyori, maintaining a temporary peace. At the same time, Ieyasu abdicated the position of Shogun to his son, Tokugawa Hidetada, thereby solidifying the hereditary succession of the shogunate.

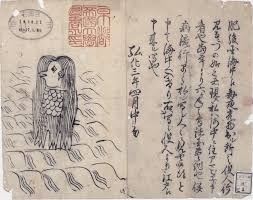

The catalyst for Tokugawa Ieyasu’s full-scale attack on the Toyotomi clan was the Bell Inscription Incident at Hōkō-ji Temple in 1614. This incident arose from the inscription on a newly installed temple bell in Kyoto’s Hōkō-ji Temple. The inscription included a prayer for the nation’s peace and security, with the phrase “kokka ankō” (“May the nation be peaceful and prosperous”).

Ieyasu interpreted the phrase “kokka ankō” as a reference to his own name, “Ieyasu,” suggesting it implied his destruction by splitting his name. Additionally, the inscription contained the phrase “kunshin hōraku shison inshō” (“May the lords and vassals enjoy prosperity, and may their descendants flourish”), which Ieyasu saw as implying the prosperity of the Toyotomi clan. He perceived this as a political challenge from the Toyotomi family.

Angered by these words, Ieyasu used the incident as a pretext to launch an attack on the Toyotomi clan in Osaka. He demanded the Toyotomi family vacate Osaka Castle, a demand they found unacceptable, which heightened tensions between the two families.

The Winter Campaign of Osaka began in November 1614. The bell inscription incident was the trigger, with Ieyasu interpreting the words as a political challenge and using them to pressure the Toyotomi clan. Ieyasu mobilized daimyo from across the country, amassing a formidable force to besiege Osaka Castle. In contrast, the Toyotomi army, supported by commanders such as Chōsokabe Morichika and Sanada Yukimura, gathered 100,000 troops, but they were outnumbered by the 300,000-strong Tokugawa army.

The Toyotomi army opted for a siege defense, taking advantage of the strong fortifications of Osaka Castle. The Tokugawa army laid siege and suffered from the Toyotomi’s counterattacks, particularly from the Sanada-maru, commanded by Sanada Yukimura, which inflicted significant damage with gunfire. However, the Tokugawa forces used advanced cannons to bombard Osaka Castle, eventually forcing the Toyotomi army to sue for peace.

The peace agreement in December 1614 appeared to bring temporary peace but was part of Ieyasu’s strategic plan. After the peace agreement, Ieyasu ordered the moats to be filled and the fortifications of Osaka Castle to be dismantled, weakening its defenses. He then demanded that Toyotomi Hideyori leave Osaka Castle or dismiss his ronin (masterless samurai). When these demands were refused, the Summer Campaign of Osaka began in April 1615.

During the Summer Campaign, Sanada Yukimura once again distinguished himself, nearly forcing Ieyasu to commit suicide. However, reinforcements arrived, allowing the Tokugawa forces to regain the upper hand. Ultimately, Osaka Castle was set ablaze, and Toyotomi Hideyori committed seppuku (ritual suicide) in a granary, assisted by Mōri Katsunaga, leading to the complete downfall of the Toyotomi clan.

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Personality

Tokugawa Ieyasu was a distinguished warrior and politician who survived Japan’s Sengoku period and founded the Edo Shogunate. One of the key elements characterizing Ieyasu’s personality is his remarkable patience. This trait was evident throughout his life, particularly during his challenging childhood and his complex relationships with other Sengoku daimyos such as Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

An anecdote that symbolizes Ieyasu’s character is often expressed in a haiku that features Nobunaga, Hideyoshi, and Ieyasu. In this haiku, Nobunaga declares, “If the cuckoo doesn’t sing, kill it,” showcasing his decisiveness. Hideyoshi says, “If the cuckoo doesn’t sing, make it sing,” highlighting his strategic approach. Meanwhile, Ieyasu states, “If the cuckoo doesn’t sing, wait for it to sing,” emphasizing his patience and willingness to wait.

Ieyasu’s patience can be largely attributed to his childhood as a hostage. At the age of six, he was sent as a hostage to the Oda clan and later transferred to the Imagawa clan, growing up in an unstable environment. These experiences taught Ieyasu to remain calm in any situation and to develop a keen sense of timing.

Moreover, Ieyasu leveraged the lessons he learned under Nobunaga and Hideyoshi to establish a governance system based on politics rather than warfare after becoming the ruler of Japan. This approach aimed at long-term stability, resulting in a peaceful shogunate that lasted for about 260 years.

Cause of Death of Tokugawa Ieyasu

Tokugawa Ieyasu died at Sunpu Castle at the age of 75. However, what was the cause of his death? There has been much debate over the years regarding the cause of Ieyasu’s death. One famous theory is that he died from overeating tempura. Ieyasu enjoyed falconry and had an active hobby, especially in his later years, when he frequently indulged in sea bream tempura at Tanaka Castle. One day, after eating too much sea bream tempura, he reportedly experienced abdominal pain that night, and his health never recovered, leading to his death. However, this is merely an anecdote, as he died three months after eating the tempura, making it unlikely to be the direct cause of his death.

From a modern perspective, the most plausible cause of death is believed to be stomach cancer. “Tokugawa Jikki” (The True Records of Tokugawa) details the symptoms Ieyasu experienced before his death, including weight loss, vomiting blood, black stools, and a large lump in the abdomen, all of which are typical symptoms of stomach cancer. Despite being very health-conscious and interested in medicine, Ieyasu is said to have compounded his illness by self-medicating rather than following his physician’s advice.

Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Episode

Let’s Take a Look at Some of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Anecdotes.

A Health Enthusiast

Tokugawa Ieyasu is known for having lived a long life for a samurai of the Sengoku period. While many samurai succumbed to injuries or illness, Ieyasu managed his health throughout his life and achieved the remarkable longevity of 75 years.

Ieyasu was considered quite the “health enthusiast.” He engaged in physical activities such as falconry, horseback riding, and swimming daily to keep his body fit, which contributed to his activity levels even in old age. He also avoided extravagant foods, preferring simple dishes such as stews, grilled foods, and barley rice, which helped him maintain his health.

Moreover, Ieyasu had a deep knowledge of herbal medicine and often compounded his remedies. He carried small containers of his medicines, such as “Manbyo-tan” and “Gin’eki-tan,” at all times. When his grandson Tokugawa Iemitsu fell ill, Ieyasu himself prepared the medicine, significantly contributing to Iemitsu’s recovery.

Ieyasu’s dedication to health management likely stemmed from the unstable environment he experienced as a hostage in his youth. The harsh living conditions taught him the importance of moderation and self-discipline. Observing close-up how other warlords like Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi led tumultuous lives and suffered from health issues may have also impressed upon him the significance of health.

A Frugal Man

Tokugawa Ieyasu is renowned for leading a life of simplicity and frugality. His frugality is evident in many anecdotes, demonstrating his economic prudence.

One story recounts that Ieyasu rarely bought new clothes and wore his existing ones until they were tattered. To reduce laundry costs, he preferred light-colored loincloths that didn’t show dirt easily. These actions illustrate his efforts to avoid waste in his daily life.

Ieyasu also practiced thrift in his meals. To save on food expenses for his maidservants, he made pickles extremely salty to discourage second helpings. His strict frugality extended to the entire household.

Another story tells of Ieyasu retrieving a piece of paper blown away by the wind rather than taking a new one, demonstrating the importance of thrift. When a retainer laughed at this, Ieyasu replied, “This is how I took the world,” emphasizing that his frugality was strategic.

Ieyasu’s frugality was also reflected in his political management. Despite the enormous revenue from his direct domains, Ieyasu allocated land sparingly to his chief retainers, which contributed to the long-term stability of the Edo Shogunate. His economic prudence and simple lifestyle laid the financial foundation for the peaceful era that lasted about 260 years.

A Studious Man

Tokugawa Ieyasu is known not only as a samurai of the Sengoku period but also for his deep scholarship and thirst for knowledge. His dedication to learning spanned various fields and was utilized in politics and strategy.

Ieyasu had a keen interest in classical literature and history, reading classics like the “Analects of Confucius,” “Records of the Grand Historian,” and “Azuma Kagami.” He also studied “The Tale of Genji” and had a profound knowledge of literature. These books provided him with lessons in politics and human relations, which he applied to his governance.

Ieyasu also had a great interest in science and technology, particularly in clocks and measuring instruments. He collected Western clocks, sundials, and hourglasses and was diligent in time management and record-keeping. Furthermore, he was the first person in Japan to use a pencil and wore glasses, which had just been introduced to Japan in 1551.

Ieyasu’s curiosity extended to foreign knowledge. He learned mathematics and geometry from “Miura Anjin” (William Adams). This learning shows that Ieyasu had a broad perspective, accepting and incorporating new technologies and cultures from home and abroad into his politics and strategies.

His interest in history was evident in his military and political strategies. He particularly studied Minamoto no Yoritomo and Takeda Shingen, learning much from their successes and failures. After the fall of the Takeda clan, he actively recruited former Takeda retainers, strengthening the Tokugawa family’s foundation.

Ieyasu’s intellectual curiosity laid the groundwork for the stable governance he established. His pursuit of knowledge was passed on to his grandson Tokugawa Mitsukuni, leading to the compilation of the “Dainihonshi” (Great History of Japan). Ieyasu’s approach to learning transcends the image of a mere warlord, presenting him as a leader with a keen intellectual quest.

The Mikawa Ikkō-ikki

Tokugawa Ieyasu faced three major crises in his life, the first being the Mikawa Ikkō-ikki in 1563. This uprising began when Ieyasu’s vassals violated the temple’s immunity from taxation, leading to a confrontation with prominent temples known as the “Three Temples of Mikawa”—Honshōji in Anjo, Jōgūji in Okazaki, and Shōmanji in Okazaki.

The Mikawa Ikkō-ikki was not merely a religious revolt but had deep political implications. The temples and their followers were dissatisfied with Ieyasu’s rule, and many of his vassals were also followers of Ikkō-shū (Jōdo Shinshū), leading to a large-scale conflict that divided his retainer group. The temples and followers’ powerful network, including farmers, merchants, transporters, and artisans, rivaled the power of a feudal lord.

The conflict, lasting from late Eiroku 6 to around March of the following year (1564), was tough for Ieyasu, but he eventually succeeded in suppressing the revolt and dismantling the Ikkō-shū temples. Despite the rift with some retainers, they were later forgiven and returned to serve Ieyasu. Among them were notable retainers like Honda Masanobu, Watanabe Moritsuna, and Natsume Yoshinobu.

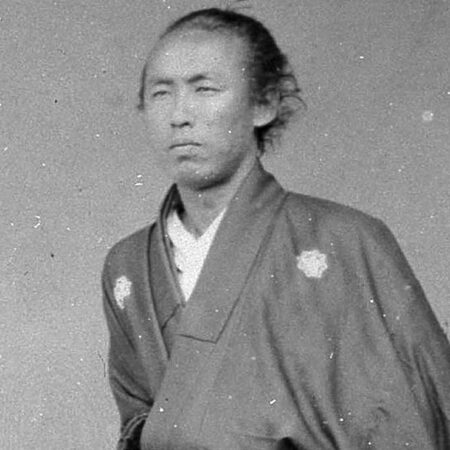

Nearly Defecating in Fear at the Battle of Mikatagahara?

In 1572, when Tokugawa Ieyasu was 31 years old, he faced another life crisis, the second of the three great crises of his life: the Battle of Mikatagahara. This year, Ashikaga Yoshiaki in Kyoto decided to break away from Oda Nobunaga and ally with Takeda Shingen. Seeing this as a golden opportunity to seize power, Shingen decided to advance to Kyoto through the province of Totomi. On this route lay Hamamatsu Castle, Ieyasu’s territory.

Ieyasu’s chief retainers advised him to hole up in Hamamatsu Castle, but Ieyasu rejected this advice and decided to confront the enemy. This decision was influenced by the belief that allowing the enemy to pass through one’s castle grounds was a disgrace to a warrior. The retainers’ assessment was that Shingen’s forces would need to return home for rice planting in the spring, avoiding a prolonged conflict. However, Ieyasu anticipated that Shingen might attack unexpectedly and decided to march out.

As it turned out, Shingen had also predicted Ieyasu’s sortie and had planned to lure him to Mikatagahara for a decisive battle. As a result, Ieyasu’s forces suffered a crushing defeat, and Ieyasu himself narrowly escaped with his life. It is said that Ieyasu was so terrified by the Takeda army that he involuntarily defecated. In the aftermath of the battle, in his regret and reflection, Ieyasu took off his armor and had an artist draw his pained expression. This painting, known as the “Portrait of Grimace,” served as a constant reminder of his defeat.

Incidentally, the last of Tokugawa Ieyasu’s three great crises was the Iga Escape following the Incident at Honnoji.

Nickname of Tokugawa Ieyasu: Tanuki Oyaji?

Tokugawa Ieyasu was nicknamed “Tanuki Oyaji” (Old Raccoon Dog). While this may seem somewhat unflattering for a great figure who unified Japan, there are several reasons behind it. Firstly, Ieyasu himself had a plump body, making the term “Tanuki Oyaji” quite fitting.

Additionally, “Tanuki Oyaji” is a term used to describe an old, cunning man. Ieyasu was nearly 60 years old when he unified the country. Furthermore, he was known to be quite crafty, deceitful, and devious. This cunning nature was famously demonstrated in the incident involving the inscription on the bell of Hokoji Temple, which led to the Osaka Winter Campaign.

Eager to find a pretext to destroy the Toyotomi family, Ieyasu seized upon the inscription on the bell, which included the phrase “kokka anko” (peace and tranquility for the nation). Ieyasu claimed that this phrase was an insult to him, as it split the characters of his name “Ieyasu,” suggesting an intent to destroy him. Using this as a pretext, he declared war on the Toyotomi family. This incident highlights Ieyasu’s deviousness.

Tokugawa Ieyasu and Nikko Toshogu Shrine

Tokugawa Ieyasu is enshrined at Nikko Toshogu Shrine in Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture. Given that it is quite far from Edo (Tokyo) and that there seems to be no significant connection to Nikko in Ieyasu’s life, why is he enshrined there?

One reason is that Nikko is located in the direction of the North Star (Polaris) from Edo. The North Star has long been a symbol of stability and constancy. By establishing his mausoleum in this direction, Ieyasu aimed to symbolize the perpetual stability and enduring rule of the Tokugawa family.

Additionally, Nikko is known as a center of mountain worship and has historically been considered a sacred place. Minamoto no Yoritomo also made donations to this area, and since Ieyasu claimed to be a descendant of the Minamoto clan, it is possible that he sought to revive the spirit of Nikko. By doing so, Ieyasu positioned himself on the same level as historical heroes, intending to elevate his own status and the authority of the Tokugawa family.

Originally, Nikko Toshogu Shrine was called “Tosho-sha,” but in 1645 (Shōhō 2), it received the title of “Toshogu.” This name means “shrine that illuminates from the east,” signifying that Ieyasu, as a deity, would illuminate and protect the entire country from the east of Japan.

Ieyasu’s grandson and ardent follower, the third shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu, undertook a complete reconstruction of Toshogu Shrine between 1634 and 1636 (Kanei 11-13), expanding its scale. This large-scale renovation, known as the “Great Kanei Renovation,” transformed Toshogu into an even more magnificent and luxurious facility, symbolizing the authority and prosperity of the Tokugawa family.

The relationship between Tokugawa Ieyasu and Nikko Toshogu Shrine reflects more than mere piety; it is deeply imbued with Ieyasu’s political ambitions, respect for history, and his enduring legacy. The spirit of Ieyasu continues to breathe in this sacred place, a reason why countless visitors still feel the profound history of the site.

Summary:

How was this overview? This article has introduced who Tokugawa Ieyasu was, along with a brief timeline, his personality, cause of death, and some anecdotes. From his experience as a hostage during childhood, he developed a remarkably patient character, eventually achieving what Oda Nobunaga had nearly accomplished—unifying Japan—and effortlessly taking over the realm that Toyotomi Hideyoshi had established, founding the Edo Shogunate and bringing about an era of stability that lasted about 260 years. His patience is also reflected in his frugality and health-conscious lifestyle.

This site introduces various aspects of Japanese history and culture besides Tokugawa Ieyasu. If you are interested, please read our other articles too!

コメント