Did you know that male-male love has been prevalent in Japan since ancient times? Surprisingly, Japan’s culture of male-male love is said to rival that of ancient Greece. Unlike Europe or China, where such relationships were often religiously monitored, Japan had a more open approach. Even some of the most famous samurai warlords are known to have enjoyed male-male love. So, how did this culture develop in Japan? Let’s explore the lesser-known history of male-male love in Japan.

History of Male-Male Love in Japan

Let’s take a look at how and when male-male love became prevalent in Japan. In Japan, “nanshoku” (male-male sexual relationships) has existed since ancient times. Records of male-male love before the Kamakura period were limited to the elite class, but from the Muromachi period onward, it spread among commoners as well. The scarcity of early records is likely because male-male love was considered natural in Japanese society at the time and was not seen as something special. This implies that such relationships were widely accepted.

Origins of Male-Male Love in Japan

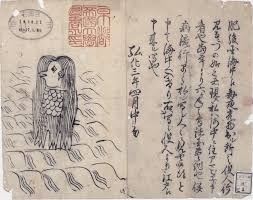

There are various theories about when male-male love began in Japan. In the early Edo period, Ihara Saikaku’s “Nanshoku Ōkagami” (The Great Mirror of Male Love) describes that Amaterasu, the sun goddess, loved Hinochimaronomikoto in a male-male relationship. Saikaku also claimed that before the birth of the divine couple Izanagi and Izanami, there were only male gods who enjoyed male-male love. According to this perspective, the history of male-male love in Japan dates back to the age of the gods.

The earliest recorded mention of male-male love appears in the “Nihon Shoki” (Chronicles of Japan), compiled in 720 CE (Yōrō 4). It includes the story of “Azunahi no Tsumi,” which involves the relationship between Shinonohafuri and Amanonohafuri. “Hafuri” refers to a Shinto priest, and it is noted that these priests were in a male-male relationship. They were described as “uruwashiki tomo” (beautiful friends), implying a sexually intimate friendship. When Shinonohafuri died of illness, Amanonohafuri followed him in death, and, as per their wish, they were buried together. This act, however, was considered a sin against the Shinto order (Amatsu Tsumi), causing darkness to fall even during the day. This story indicates that it was not the male-male relationship itself that was considered a sin, but rather the ritualistic issue of burying the priests together.

Popularity of Male-Male Love in Temples and the Imperial Court

References to male-male love can be found in famous works such as the “Nihon Shoki,” “Manyoshu,” and “The Tale of Genji,” indicating that male-male love was widely accepted. While there is a theory that Kukai introduced male-male love to Japan, this is considered a popular misconception since references to male-male love exist from before Kukai’s return to Japan in the early Heian period. However, it is true that Kukai’s influence contributed to the spread of male-male relationships between monks and their young acolytes (chigo).

During the Nara period, monks frequently read the Buddhist scripture “Shibunritsu,” which includes prohibitions against sexual acts (inkai), banning all forms of sexual activity regardless of gender. However, as Buddhism generally harbored a strong aversion to sexual relations with women, a culture gradually developed that tolerated male-male love. The sexual acts with chigo were justified within Buddhism by turning the acts into a ritual called “chigo kanjo,” a ceremony that deified the chigo, thus legitimizing male-male love within the religious framework.

The relationship between monks and chigo is also depicted in the “Goshūi Wakashū,” an imperial anthology of waka poetry, demonstrating that such relationships were widely accepted and tolerated enough to be included in a collection compiled by imperial order. Moreover, at the imperial court, it was not uncommon for nobles to keep beautiful chigo by their sides and share their beds with them.

Samurai Male-Male Love Culture: “Shudō”

As samurai increased their power, male-male love also became prevalent within samurai society through interactions with aristocrats and monks. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, who led the Muromachi Shogunate and unified the Northern and Southern Courts, actively incorporated various cultural aspects from the nobility and clergy, including male-male love. He is credited with laying the foundation for the samurai-specific male-male love culture known as “shudō.”

“Shudō” refers to the bonds of male-male love between a lord and his young page (koshō), emphasizing not only physical but also spiritual connections. Male-male love was recognized as a ritual to establish relationships of absolute loyalty and strong bonds. Although the precursors of shudō can be seen in the late Heian period during the Genpei War, shudō culture truly flourished during the Sengoku period.

At that time, many samurai went to battle, leaving their wives and children behind. In the absence of women, it was easy to see men as sexual objects. There are accounts of samurai being killed by beautiful boys using seduction techniques known as the “Katsura-otoko no jutsu” during spy missions.

Male-Male Love Among Commoners

During the Muromachi period, male-male love also spread among commoners. The noh drama “tezarugaku,” enjoyed by commoners, gave rise to “chigo sarugaku,” featuring beautiful boys who entertained many people at banquets and sometimes spent the night with them.

Missionary Francisco Xavier lamented in his letters to his homeland about the difficulty of explaining the sin of male-male love to the Japanese, who practiced monotheism and monogamy. In Japan, male-male love was accepted across all social classes, including monks.

Even in the Edo period, male-male love was considered as normal as loving women. Young kabuki actors, known as wakashū kabuki, began engaging in prostitution at banquets, leading to the emergence of male prostitutes called “kagema.” These male prostitutes served not only monks and samurai but also many commoners, including farmers and craftsmen. Korean envoy Shin Yu-han, who visited Japan during the Edo period, noted in his book “Haiyurok” that male prostitutes’ allure sometimes surpassed that of women.

The Taboos Influenced by the West

Before the Edo period, male-male love in Japan was socially accepted, and male sexual relationships were not discriminated against as “perversion,” sexual abnormality, or illness. However, during the Meiji era, as Japan modernized, Western sexology and views that stigmatized homosexuality influenced Japanese attitudes, leading to the marginalization of male-male love as “perversion” or “sexual deviation.” Men in same-sex relationships could even face legal punishment. Consequently, male-male love gradually became taboo.

Initially, during the Meiji period, male-male love was considered preferable to indulging in women, and the culture of male-male love remained among students pursuing “stoicism.” However, in 1873 (Meiji 6), the “keikan” law criminalizing male-male sexual relations was enacted. At the time, Japan aimed to catch up with Western powers, so it could not condone male-male love, which was taboo in Western countries. Although the “keikan” law was abolished in 1882 (Meiji 15), the idea of male-male love as a sin grew stronger in the late Meiji period. By the Taisho period, Western ideas had further penetrated Japan, and male-male love began to be treated as a “disease.”

Famous Figures Known for Male-Male Love

Given this historical background, male-male love became widespread in Japan. So, who were some of the notable figures known to have engaged in male-male love? Here, we introduce some famous individuals and how their male-male relationships even led to the creation of well-known systems.

Fujiwara no Yorinaga

Fujiwara no Yorimichi, who succeeded Fujiwara no Michinaga and enjoyed the peak of regency politics, was also known for his preference for male-male love. In the “Kyokunsho,” the oldest Japanese book on court music and dance written in the Kamakura period, it is depicted that Yorimichi was captivated by the dance of a beautiful boy named Minemaru during a Buddhist ceremony at his villa, the Byodoin in Uji.

Additionally, the “Kojidan,” a collection of stories from the early Kamakura period, records that Minamoto no Nagatsune, a retainer of Yorimichi, was also his lover. Thus, Yorimichi’s preference for male-male relationships was widely known.

Furthermore, Yorimichi’s grandson, Fujiwara no Yorinaga, also had a fondness for male-male love. Yorinaga, who died from wounds sustained in the Hōgen Rebellion, is said to have had relationships with as many as seven nobles. Nobles of that time had a custom of keeping diaries, and Yorinaga detailed not only court ceremonies but also his private life.

In his diary, the “Taiki,” Yorinaga vividly described the pleasure he derived from male-male love and his infatuation with young boys. Notably, his direct expressions of joy in “leaking semen together,” meaning “ejaculating together,” are quite surprising. Yorinaga’s accounts provide a rare glimpse into the aristocratic society of his time and serve as valuable historical documents.

Oda Nobunaga

Oda Nobunaga, one of the most famous figures in Japanese history, is also said to have had experiences with male-male love. His most famous partner was Mori Ranmaru. Known for his handsome appearance from a young age, Ranmaru was highly favored by Nobunaga. Nobunaga had Ranmaru attend to his personal needs and also assigned him secretarial duties.

Additionally, there is a theory that Nobunaga may have had a male-male relationship with Maeda Toshiie. Thus, Nobunaga’s relationships with multiple individuals have been noted, adding an intriguing aspect to his private life.

Takeda Shingen

Takeda Shingen, known as the most powerful samurai during the Sengoku period, is also said to have had experiences with male-male love. His famous partner was Kosaka Masanobu. From a young age, Masanobu was known for his handsome appearance, and Shingen was very fond of him.

It is said that on one occasion, when Shingen had an affair with another person, he sent a letter of explanation to Masanobu. This letter reportedly read like a love letter. This episode further illustrates the depth of the relationship between Shingen and Masanobu.

Date Masamune

The Sengoku warlord Date Masamune, known as the “One-Eyed Dragon,” is also said to have had experiences with male-male love. His famous partner was Katakura Shigenaga. There is a notable anecdote from before the Siege of Osaka, highlighting the bond between Masamune and Shigenaga.

Before Shigenaga’s first battle, he asked Masamune to let him lead the charge to uphold the honor of the Katakura family. Masamune, moved to tears, agreed, saying, “I wouldn’t let anyone else lead the charge but you.” This story exemplifies the deep bond and affection between Masamune and Shigenaga.

Tokugawa Ieyasu and Tokugawa Iemitsu

Tokugawa Ieyasu, who conquered the Sengoku period and became the ruler of Japan, also has episodes of male-male love. Although Ieyasu generally preferred older women, the “Kōyō Gunkan” records that he was captivated by the beauty of his loyal retainer, Ii Naomasa, and had a relationship with him.

Similarly, there are stories about the third shogun of the Edo Shogunate, Tokugawa Iemitsu, who supposedly became averse to women due to a bitter experience before his coming-of-age ceremony. However, as a shogun, producing heirs was an important duty. Worried about this, the influential Kasuga no Tsubone dressed Iemitsu’s concubines in the attire of young male pages to attract his interest. It is said that Iemitsu’s preference for male companionship later led to the establishment of the Ōoku.

Matsuo Basho

The famous haiku poet Matsuo Basho often traveled with his disciples, and it is said that he had romantic relationships with two of them. While “Oku no Hosomichi” (The Narrow Road to the Deep North) is well-known, Basho’s travelogue “Oi no Kobumi” (The Record of a Travel-Worn Satchel) describes his journeys with his beloved disciples, Tokoku and Etsujin.

During his travels with Etsujin, Basho composed a romantic haiku: “Though it is cold, I find comfort in the night we sleep together.” Similarly, when with Tokoku, he wrote, “In the solitude of the grass pillow, the two of us find solace in our conversations.” These verses suggest Basho’s enjoyment of traveling with his beloved companions.

Views on such relationships vary by country and region, and they have changed significantly over time. What was once considered normal in Japan may have become taboo, and vice versa. Understanding the history of male-male love in Japan prompts us to reconsider what is deemed “normal.”

Summary

How was it? As we have seen, the history of male-male love in Japan is rich and varied, spanning from ancient to modern times. In ancient and medieval periods, male-male relationships were widely accepted across all social classes, from the elite to commoners, and were considered natural. Such relationships were integrated into the culture and rituals of temples, the imperial court, and samurai society, leaving traces in many historical texts and stories. However, during the Meiji era, as Japan westernized and modernized, Western sexology and the stigmatization of homosexuality influenced Japanese views, leading to the marginalization of male-male love as “perversion” or “sexual deviation.”

Our site features various fascinating aspects of Japanese history and culture beyond male-male love. If you’re interested, we hope you’ll read our other articles as well!

コメント