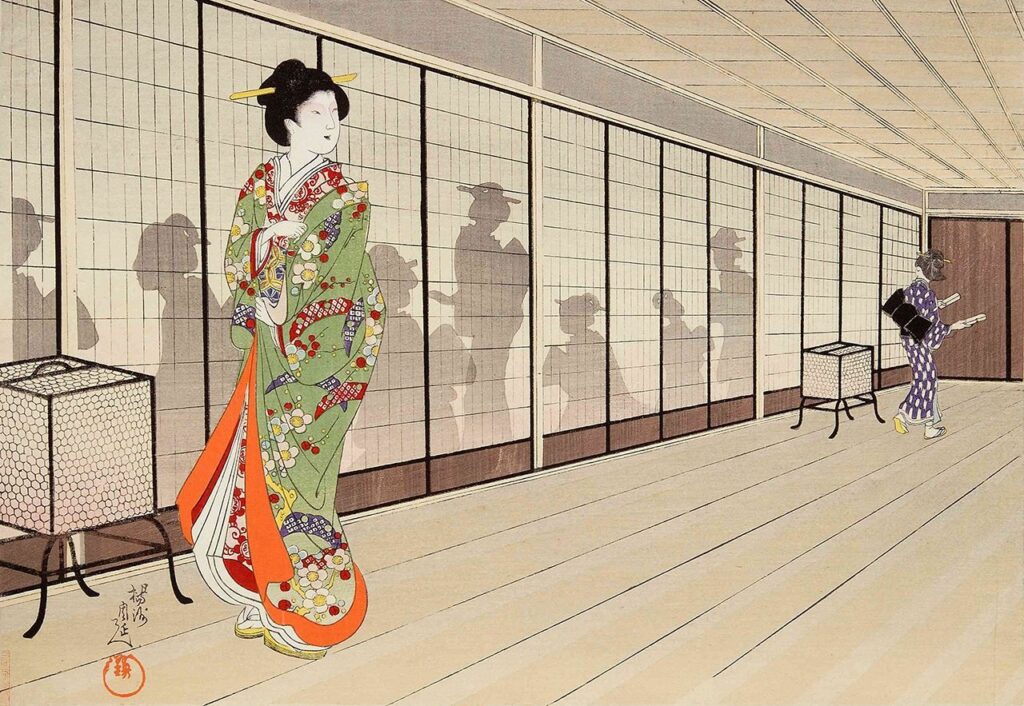

Have you heard of the Ōoku? It was a secret garden that actually existed during the Edo period, said to have housed “3,000 beautiful women” who served the shogun. It was a world forbidden to men, with only the shogun being allowed to enter. The reality of the Ōoku is shrouded in mystery. However, in reality, there were very strict rules regarding intimacy in the Ōoku. It is said that the shogun had to engage in nighttime activities while being eavesdropped on. This time, we will thoroughly introduce you to the little-known secret garden, the Ōoku.

What is the Ōoku?

The Ōoku was a section within Edo Castle where the wives and children of the shogun of the Edo Shogunate lived, along with the women who took care of their needs, known as “Ōoku attendants.” The concept of the Ōoku originally came from the idea of the “omote,” which referred to the public, political areas of samurai residences, and the “oku,” which referred to private, living quarters. Within Edo Castle, this living space was specifically called the “Ōoku.”

The establishment of the Ōoku dates back to the time of Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun of the Edo Shogunate. During this period, many attendants were gathered in the Ōoku to ensure the continuation of the shogun’s bloodline, performing various roles. The number of attendants in the Ōoku is said to have ranged from 1,000 to 3,000, though the exact number is unknown.

Edo Castle was divided into four main sections: Honmaru (the main compound), Ninomaru (the second compound), Sannomaru (the third compound), and Nishinomaru (the western compound). The Ōoku was located in Honmaru and Nishinomaru. Honmaru was further divided into three sections: the Omote, where the shogun conducted governmental affairs; the Nakaoku, which served as a residence; and the Ōoku, which was divided into the Goten (residence), Nagatsubone (long corridors), and Ohiroshiki (large rooms).

Purpose of the Ōoku

The primary purpose of the Ōoku was to ensure that a male heir related by blood to the shogun would succeed the position. At that time, there was an unwritten rule that the next shogun had to be a male related by blood to the previous shogun.

As such, during a time when polygamy was common, it was most desirable for the shogun’s official wife (principal wife) to bear a son. However, if this was difficult, it was strongly expected that a concubine (a wife other than the principal wife) would bear a son. The existence of the Ōoku provided a system where numerous women could live together to fulfill this purpose.

Women in the Ōoku played various roles to ensure the shogun’s bloodline did not die out. They served as official wives and concubines, playing crucial roles in supporting the prosperity of the shogunate family. Thus, the Ōoku functioned as an essential institution supporting the stability of the Edo Shogunate and the continuity of the shogunate family.

A Brief History of the Ōoku

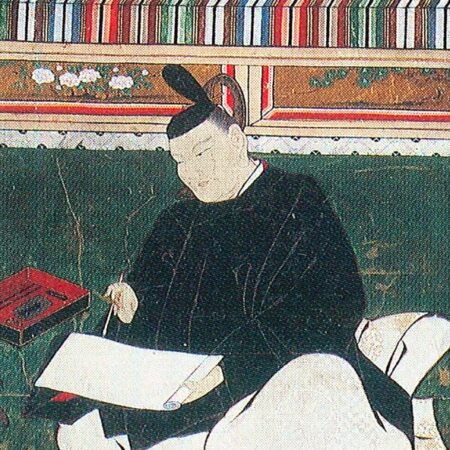

Edo Castle was originally built by the Sengoku period warlord Ōta Dōkan. The castle began to be used as the residence of the shogun in earnest from the time of Tokugawa Hidetada, the second shogun. It was Hidetada’s wife, Lady Oeyo, who first established the women’s quarters in the innermost part of the main compound. Lady Oeyo was the niece of Oda Nobunaga and was also famous as a princess of the Sengoku period. She was also known as “Gō” and became the protagonist of a historical drama.

Hidetada, fearing Lady Oeyo’s jealousy, ordered pregnant women to leave Edo Castle and give birth elsewhere. The children born in this manner were then entrusted to retainers. One such child was Hoshina Masayuki, who later became the lord of Aizu Domain and the founder of the Aizu Matsudaira family.

The Ōoku was formally established, and women began to be gathered there from the time of Tokugawa Iemitsu, the third shogun. Iemitsu was known for his preference for male lovers, causing concern that there might not be an heir to the shogunate. It was Iemitsu’s wet nurse, Kasuga no Tsubone, who gathered women who might appeal to Iemitsu, marking the beginning of the Ōoku. There is a legend that at its peak, the Ōoku housed as many as 3,000 beautiful women.

Iemitsu was not entirely averse to women, as he had several concubines and fathered six children. Among these women was Otama no Kata, the daughter of a greengrocer, who became Iemitsu’s concubine and later gave birth to Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, the fifth shogun. Her rise to prominence is the origin of the term “Tama no Koshi,” meaning to marry into wealth.

Were There Really 3,000 Beauties in the Ōoku?

There is a legend that the Ōoku housed “3,000 beauties,” but this is an exaggeration. This legend was modeled after the Chinese phrase “Harem of 3,000 beauties” and is a symbolic expression indicating that many women were gathered there. In reality, the Ōoku had about 400 attendants, known as “oku-jōchū,” and including the personal servants (heya-ko) employed by higher-ranking attendants, it is estimated that around 700 to 800 people lived there. This is still quite a large number.

The number of attendants needed in the Ōoku varied depending on the era and circumstances. It also depended on the number of concubines and children, resulting in fluctuations in the population at different times. For instance, Tokugawa Yoshimune, the eighth shogun who implemented the Kyōhō Reforms, carried out a unique reform in the Ōoku by gathering only the most beautiful women and dismissing them, suggesting that they had better marriage prospects elsewhere.

The Ōoku was not only located in the main compound of the castle but also in the secondary and western compounds, where the next shogun or the wife of the previous shogun might reside. In this way, the Ōoku was flexible and adapted to the times and circumstances.

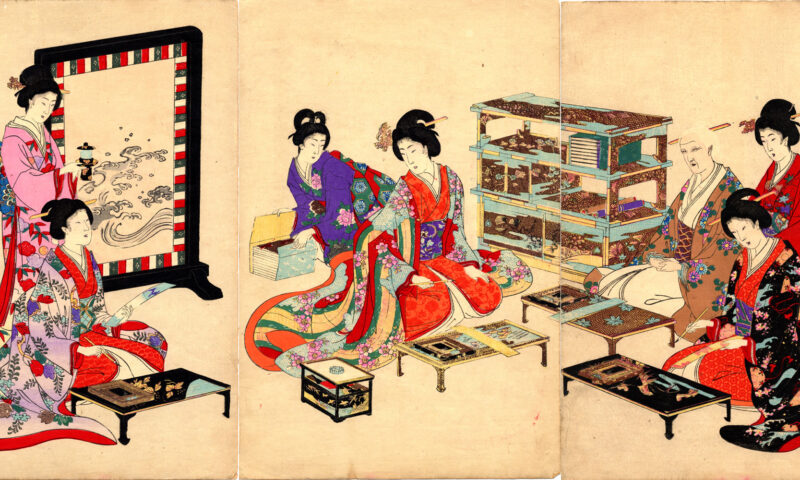

The Organization of the Ōoku

The Ōoku had two types of women: career and non-career groups. The career women, known as “O-memie Ijō,” had the privilege of meeting the shogun directly, while the non-career women, called “O-memie Ika,” did not. The women of the Ōoku performed various roles, from taking care of daily chores and cleaning to holding important positions that oversaw the entire Ōoku.

At the top of the hierarchy were the “Jōrō Otoshiyori” (Senior Elders), who often accompanied the shogun’s official wives, especially those who came from the court nobility after Iemitsu’s era. These women played crucial roles as companions and advisors to the shogun’s wife.

Next in rank were the “O-toshiyori” or “Rōjo” (Elders), comparable to senior advisors in the shogunate’s administration. They were responsible for the actual management and supervision of the Ōoku, and many women in their 30s to 40s held these positions. It’s noteworthy that in that era, women in their 30s to 40s were referred to as “elderly.”

The “O-chūrō” were responsible for attending to the personal needs of the shogun and his wife. Among them, the role of “Otogi” (bedtime companion) was especially significant, as they were chosen from among the shogun’s personal attendants. If the shogun did not appoint a specific Otogi, it was typically the O-toshiyori who made the selection.

Advancing in the Ōoku was described as requiring “One pull, two luck, three women,” meaning that being promoted by a powerful O-toshiyori or having a vacancy arise was more important than beauty. Thus, the organizational structure of the Ōoku was complex, with many women fulfilling various roles to support the shogun’s household.

The Ōoku demonstrates that women played important roles and were systematically organized in that era. Each position had specific duties, and the entire Ōoku operated with order and discipline. In this way, the Ōoku played a crucial role in supporting the prosperity and stability of the shogunate family.

Was the Ōoku Off-Limits to Men?

The Ōoku generally prohibited the entry of men, except for the shogun. This strict rule ensured that the shogun’s heir was undoubtedly his biological child, given that DNA testing did not exist at that time. Even the male relatives of the Ōoku attendants were allowed to meet them only until the age of nine. Interestingly, Katsu Kaishū, a notable historical figure, once lived in the Ōoku due to his familial connections with an Ōoku attendant.

However, in reality, some adult men other than the shogun did enter the Ōoku. Shogun’s children who were adopted by other daimyo families could return to the Ōoku as if visiting their family home. Additionally, heads of the three collateral Tokugawa branches (the Tayasu, Hitotsubashi, and Shimizu families) were allowed to enter the Ōoku because they were considered part of the Tokugawa family.

Moreover, men who performed certain duties also had access to the Ōoku. Senior counselors (Rōjū) of the shogunate would enter when summoned by the shogun’s official wife (Midaidokoro) or for conveying appointments and exchanging information with the Ōoku attendants. Physicians attending to the shogun, carpenters for repairs, and artists painting sliding screens also entered the Ōoku.

There were also men whose workplace was within the Ōoku itself. Chief among these were the “Rusuiyaku” (caretakers). Initially, they were in charge of guarding Edo Castle when the shogun was away at war, but the position later became permanent, and they took on roles such as overseeing the Ōoku. Under the Rusuiyaku were the “Hiroshiki-muko” officials, who handled administration and security in the Ōoku. These included the “Hiroshiki-yōnin” (administrative officers), “Hiroshiki-yōtashi” (supervisors), “Hiroshiki-zamurai” (guards), and “Hiroshiki-goyōbu-shakuyaku” (clerks).

Furthermore, under the chief of the Hiroshiki, the “Hiroshiki-ban-no-kami,” were “Hiroshiki-soe-ban” (assistants), “Hiroshiki-ban-nami” (junior officers), “Hiroshiki-iga-mono” (guards), and “Hiroshiki-gedō” (servants). These servants often received food and goods from the Ōoku attendants in exchange for running errands and were rumored to be invited into the attendants’ rooms. The “Kurokuwa-no-mono” (black hoe workers) who carried out tasks like transporting goods, performing construction work, and cleaning the moats within Edo Castle also entered the Ōoku. These workers often received gratuities from the attendants and could live relatively well.

Thus, while the Ōoku was predominantly a world of women, many men were involved in various roles to support its operation and maintenance.

Strict Intimacy Rules of the Ōoku

The shogun’s intimate encounters in the Ōoku followed strict rules and rituals. On the day the shogun wished to visit the Ōoku, he would first inform the “Otogi Bōzu” (attendant monks). It was common for the shogun to designate a specific attendant for his visit. The curfew for the Ōoku was set at 6 PM, and the shogun had to enter the Ōoku by that time.

The term “Otogi” means “to attend in the sleeping quarters,” and the Otogi Bōzu were veteran attendants responsible for overseeing the shogun’s intimate activities. They were called “Bōzu” because they had shaved heads. Regardless of how favored an attendant was by the shogun, there was a rule called “Oshitone Gomen,” where an attendant would retire from being a bed partner at the age of 30. This rule was initially intended to avoid the risks associated with childbirth at an older age, especially for the official wife (Midaidokoro), but it also applied to concubines and attendants. Retired attendants often had surprising roles awaiting them.

The summoned attendant would change into a white kimono (shiro-muku) and tie her hair with a comb instead of using hairpins. Accompanied by several other attendants, she would enter the adjoining room of the sleeping quarters, where she underwent a thorough physical examination. Even her hair was meticulously checked, and then it was tied up again with a comb.

Once the shogun and the attendant began their intimate activities, senior attendants, including the Otoshiyori, Otogi Bōzu, and other attendants, closely monitored the situation. This was to prevent the attendant from making demands of the shogun, such as requesting that her child be made the next shogun if she bore a son. The role of “Osotoneryaku” involved staying awake all night and listening in, reporting the events of the night to the Otoshiyori in the morning. This role could also be fulfilled by women who had retired from being the shogun’s partner.

In the morning, detailed reports were given to the highest-ranking officials in the Ōoku, the Otoshiyori. This entire process was a strict ritual, ensuring that all aspects of childbearing were under rigorous supervision.

Although the rules were not as stringent when the partner was the Midaidokoro (the shogun’s official wife), monitoring still took place according to common belief.

Was the Ōoku Really a Harem?

When people hear about the Ōoku, they often imagine a nightly world of indulgence and excess for the shogun. However, the reality was quite different. The Ōoku was governed by strict rules, and as previously mentioned, the shogun’s intimate activities were constantly monitored, leaving little privacy.

The shogun could not visit the Ōoku every night. One of the shogun’s official duties was to visit the tombs of previous Tokugawa shoguns on their monthly memorial days. On the day before these visits to temples such as Kan’ei-ji in Ueno or Zōjō-ji in Shiba, the shogun was forbidden to stay in the Ōoku to purify himself. As a result, during the late Edo period, the shogun’s schedule was so packed with official duties that he could only stay in the Ōoku about half of the month.

Moreover, the shogun could not freely choose any woman he desired. Although there were hundreds of women in the Ōoku, the shogun’s interactions were limited. The women he regularly interacted with were primarily the “O-chūrō,” the attendants who were in close service to him, and the night companions were typically chosen from among them.

Additionally, the shogun’s intimate encounters were highly formalized. The summoned attendant would change into a white kimono (shiro-muku) and undergo a strict physical examination. During the intimate act, senior attendants, including the Otoshiyori and Otogi Bōzu, monitored the proceedings, and a detailed report was made the following morning. This strict oversight prevented the attendant from making unreasonable demands of the shogun.

For the shogun, the Ōoku was not a place of freedom but a space where he had to live under numerous constraints and regulations. His private life was highly controlled, and even his nightly activities were conducted under strict surveillance. Due to his official duties and these regulations, life in the Ōoku was far from the lavish and carefree existence that people might imagine.

Did the Ōoku Cost a Lot of Money?

During the Edo period, the shogunate repeatedly issued austerity measures to rebuild its finances. Among these, the maintenance costs of the Ōoku were a significant issue. With each successive shogun, the expenses of maintaining the Ōoku increased, becoming a major factor in the financial strain on the shogunate.

During the time of the 8th shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, the Ōoku was downsized as part of financial reforms. Yoshimune implemented a bold reduction plan, laying off fifty of the most beautiful women from the Ōoku, reasoning that they would have no trouble finding suitable marriages. This move was intended to curb the expansion of the Ōoku and alleviate financial pressures.

Further reforms were carried out during the time of the 14th shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi. The tobacco expenses of his wife, Princess Kazu-no-miya, reached about 105 ryō per month (approximately 12.6 million yen in today’s value), but these were reduced by 90% to 10 ryō 2 bu (about 1.26 million yen). Despite these intermittent reforms, the maintenance costs of the Ōoku continued to burden the shogunate’s finances.

Ultimately, before these reforms could fully take effect, the Meiji Restoration occurred, leading to the end of the shogunate and the closure of the Ōoku.

Summary

How was it? This time, we looked at the overview, brief history, and strict rules of the Ōoku. The Ōoku was established during the reign of Tokugawa Iemitsu, partly due to his preference for male companionship, to ensure the continuation of the shogunate lineage by securing male heirs. The Ōoku had surprisingly strict rules regarding intimacy, stay duration, and curfews. It is ironic that such an institution also contributed to the financial strain on the shogunate.

コメント